The grave of Salome Carto in Perry’s Mills, NY

Source: author’s personal collection

A weathered tombstone in a small cemetery in Perry’s Mills, New York, marks the final resting place of Salome Carto. To a passerby, it may seem like any other headstone in a small cemetery. Yet beneath it lies the story of a woman who weathered the hardships and turbulence of her century with extraordinary resilience.

Born Marie Salomée Boire on April 24, 1823, in Saint-Philippe, Quebec, Salome faced challenges at a young age. When she was only eleven, her father died, a tragedy that forced her widowed mother to hold together a household in an era when death often came early. By her teenage years, Salome had crossed the border into northern New York with her family, joining thousands of French Canadian migrants who would eventually seek farmland and opportunity just south of the border while still remaining close to their kin.1

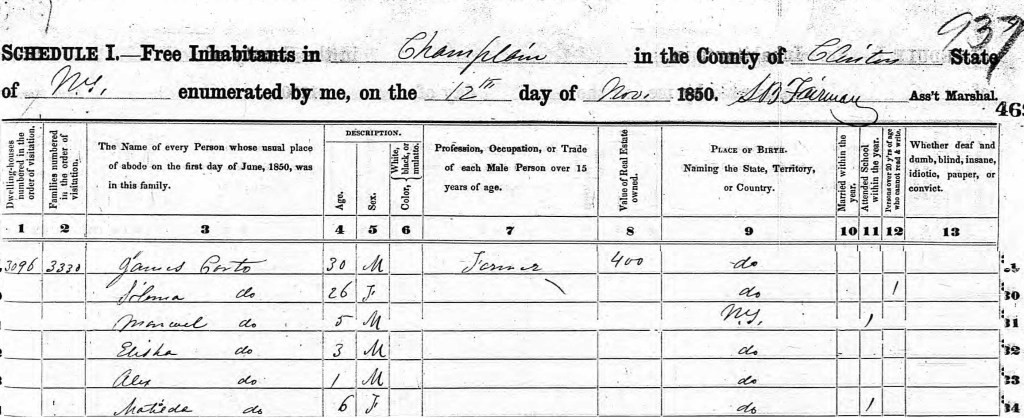

The first appearance of James and Salome’s family in the federal census in 1850.

Source: 1850 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township.

At twenty, Salome married James Carto, a Canadian-born farmer, and settled in Perry’s Mills, a hamlet of Champlain where stony fields and small barns defined daily life. When the census taker called in 1850, the Cartos lived on a farm valued at $400 and had four children under the age of six: Mathilda (age 6), Manny (age 5), Elisha (age 3), and Alex (age 1).2 The family would expand with the arrival of daughter Amelia in 1851 and daughter Cornelia in 1857. Salome’s life as a mother of seven young children living on a rural farm would have been defined by arduous and constant cycles of domestic labor and emotional strain. Nineteenth century households were complex economic units, and as its manager, Salome was responsible for a myriad of tasks critical to the family’s survival, including food preservation, textile production, and childcare, all performed without modern conveniences. This demanding workload of farm life was always precarious. A sick cow, a bad harvest, or the loss of a child could throw the household into crisis. And for Salome, loss was never far away. Of her seven children, two—Manny (in 1851) and Cornelia (in 1861)—died before they reached school age. The empty chairs at the family table told a story repeated in countless rural homes, where two in five children never survived to see adulthood.3

The Carto farm remained modest in 1860—just sixteen acres of worked land, at a slightly improved value of $500, a fraction of what most neighbors reported.4 The Cartos owned a handful of livestock—three horses, a cow, nine sheep—and relied on every member of the family to keep the place running. Children were not simply raised; they were put to work. Historian Steven Hahn has written that northern farm families leaned on “the labor of sons and daughters to maintain productivity, diversify tasks, and ensure continuity across the seasons.”5 For the Cartos, that meant sons planting oats and potatoes, daughters churning butter and tending animals, and Salome overseeing it all.6

The start of the Civil War added yet another burden to this fragile existence lived by the Cartos. Christmas 1863 saw Eli, Salome’s oldest but barely sixteen-year-old son, enlist in the Union Army after the conclusion of harvest. He went with his uncle Eleazor, perhaps emboldened by the tales of another uncle, Jerome, who had returned from Antietam maimed but alive. The young men joined the 16th New York Cavalry, a regiment sent not to the great battlefields, but to the thorny guerrilla war in northern Virginia. Their task was to track down Confederate ranger John Mosby, whose men seemed to strike from the shadows. As the commander of the 16th New York Cavalry noted about one engagement, “Small parties were seen about Leesburg, but would scatter to the woods when pursued.”7 For Salome, days stretched into months of worry. Then, in March 1865—just weeks before Appomattox—Eli was killed in Virginia in a small skirmish that is barely a footnote in the War of the Rebellion official records. His body never came home.8 The war ended soon after, but victory brought no comfort to a mother who had lost her eldest son. His absence was more than emotional: it left one less pair of hands to keep the Carto farm alive.

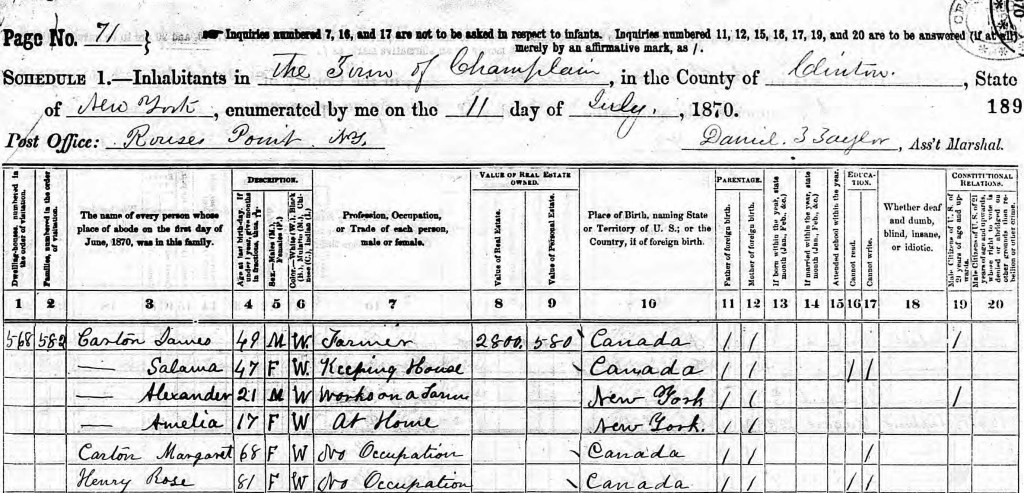

The Carto family had expanded by 1870 include the mothers of both James and Salome

Source: 1870 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township.

Despite this devastating loss, the Carto family demonstrated remarkable resilience and an ability to adapt during the post-war period. The 1870 census reveals significant changes in the Carto farm. James, now with the help of his surviving son Alex, had doubled their improved land to 40 acres and increased the total value of the farm from $500 to $2,600. Their livestock holdings grew to 3 horses, 2 cows, 1 other cattle, 2 sheep, and 8 swine, with a total livestock value of $250. This expansion allowed them to increase their production of wheat, corn, oats, and potatoes as well. Most notably, their yearly butter production soared from 40 pounds in 1860 to 160 pounds by 1870, a significant increase that highlights the family’s intensified focus on dairy, while also producing 25 pounds of maple sugar and 125 pounds of honey to diversify their income sources.9 This pivot required more work for everyone, especially Salome and her daughters.

The 1870s introduced another dynamic for the Cartos: providing for James’s mother, Margaret, and Salome’s mother, Rose. In the nineteenth-century United States, it was common for households to expand in this way, as families were the primary source of care and support for aging relatives.10 While this arrangement reflected prevailing cultural expectations, it also added new burdens to the household, complicating Salome’s already demanding work of coordinating care, labor, and resources within the family.

The 1870s brought other changes for Salome and her family. Male members of the Carto household increasingly pursued employment outside the home. James, remembered locally as “our old stand-by bridge fixer,” was repeatedly compensated for his work maintaining bridges in Perry’s Mills.11 Meanwhile, Alex earned wages as town constable.12 While this work undoubtedly helped the Carto family expand the wealth of their household, it also likely meant that Salome’s role as supervisor of the household economy became more critical. The decade further marked the first recorded instance of the Cartos subscribing to a local newspaper.13 This development is particularly striking given that both James and Salome consistently reported on federal censuses that they could neither read nor write. Although the precise reason for their subscription remains unknown, it may reflect several possible motivations: a desire for access to information beyond their immediate community, an interest in political affairs, or an intention to provide reading material for their children.

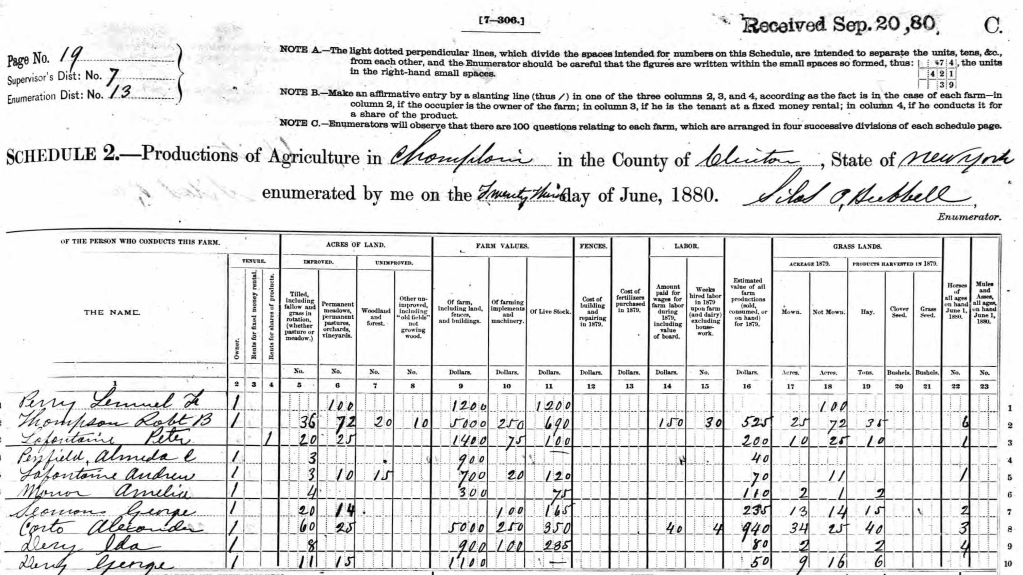

The 1880 agricultural census reveals the complexity of the farm that Salome would soon run on her own.

Source: 1880 U.S. Census, Agricultural Schedule, Town of Champlain, Clinton County, New York.

By 1880, the Carto farm had undergone yet another decade of expansion and transformation. The acreage of improved land rose to 60 acres, and the total value of the farm nearly doubled again to $5,000, with additional investments in machinery and livestock. Their herds grew to include four milk cows and a larger number of young cattle, reflecting a stronger emphasis on dairying; over 900 gallons of milk were sold to factories in 1879, signaling a shift from small-scale butter making toward commercial milk production. Grain cultivation diversified to include barley and buckwheat alongside oats, wheat, and corn, while hay fields and seed production demonstrated careful management of the farm’s grasslands. Potatoes and apples were raised for both subsistence and market sale, and poultry flocks provided a steady supply of eggs. The insight from 1880 portrays a farm that had not only stabilized but grown more prosperous, combining traditional mixed farming with a new commercial orientation in dairy and diversified crops. The most telling sign from the census was that the family reported hiring farm labor in 1879.14

Circumstances changed markedly for Salome during the 1880s, severely testing her resilience. In 1880, James died, leaving her a widow at fifty-seven. Her son Alex temporarily assumed management of the farm, but he succumbed to tuberculosis in November 1881. The burden deepened when Alex’s young wife, Virginia, died of the same disease in June 1882. Tuberculosis, which haunted so many rural households in the nineteenth century, left two little girls—Clarissa (b. 1878) and Cornelia (b. 1880)—without parents. At an age when many women might have expected to lean on grown children, as James and Salome had once provided for their own elderly mothers, Salome instead became the sole head of a household with two children under four where the weight of survival fell squarely on her shoulders. She rose each morning not only to tend her few acres but to guide two young girls through a childhood shaped by absence. In the post war period, widows and older women often assumed new responsibilities as heads of households, bridging the needs of younger generations while sustaining the economic life of the family.15 Salome’s experience echoed this wider pattern, turning her home into a place where caregiving and subsistence labor merged in the wake of loss.

The absence of census records for 1890 obscures a full picture of Salome’s final years. Nonetheless, scattered documentary evidence offers glimpses into the life she sought to provide for her granddaughters. A pivotal development came with the passage of the Dependent and Disability Pension Act of 1890, which extended benefits to mothers of fallen soldiers. In June 1894, Salome successfully applied for and received a modest pension based on Eli’s service.16 While the amount was limited, it carried a deeper significance: formal recognition that her son’s sacrifice—and, by extension, her own—was valued by the nation. Around this time, newspapers reported that Clara enrolled at the Plattsburgh Normal School.17 This fact further supports the notion that Salome valued education and sought to open educational opportunities for her granddaughters.

Salome’s granddaughter Clara Carto circa 1898

Source: Provided to author by family member.

By the turn of the century, Salome’s granddaughters had grown into young women. Clara became a teacher, one of the few professional paths open to women at the time, while Cornelia remained at home. Salome reported in 1900 that she had given birth to seven children, but only two remain alive.18 This final disclosure underscores the profound experiences of loss that marked her life, including the death of at least one child absent from surviving historical records.

Salome’s final appearance in the historical record came in March 1903, when her granddaughter Cornelia married Richard Upton in Perry’s Mills. A local newspaper noted that “The service was performed by Rev. H. C. Petty, and was witnessed by only the immediate relatives of the contracting parties.”19 Less than two months later, on May 16, Salome passed away, having lived long enough to see her granddaughter wed. She was laid to rest in Perry’s Mills, the village where her life had unfolded amid decades of hardship and endurance.

Salome life, though largely absent from public records of distinction, reflects the quiet endurance of many nineteenth-century rural women whose labor, resilience, and grief were borne largely within the domestic sphere. Salome’s persistence amid repeated loss, her role in sustaining her household, and her care for successive generations position her story as part of the broader narrative of women’s indispensable yet often unacknowledged contributions to family and community life.

- 1900 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, page 25, family 362, Salame Carto household; digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing FHL microfilm: 1241018. ↩︎

- 1850 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, dwelling 3096 family 3330, James Carto household; digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M432, 1009 rolls. ↩︎

- Michael R. Haines, Estimated Life Tables for the United States, 1850-1900 (September 1994). NBER Working Paper No. h0059, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=190396 ↩︎

- 1860 U.S. Census, Agricultural Schedule, Town of Champlain, Clinton County, New York, Page: 7; Line: 32, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025). ↩︎

- Steven Hahn, The Roots of Southern Populism: Yeoman Farmers and the Transformation of the Georgia Upcountry, 1850–1890 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 23–26. ↩︎

- For information regarding the shifting family dynamic from a patriarchal system to one where women, as mothers, were increasingly responsible for the moral and emotional development of their children, see Mary P. Ryan, Cradle of the Middle Class: The Family in Oneida County, New York, 1790-1865. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981. ↩︎

- Nelson B. Sweitzer, report of March 14, 1865, in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, ser. 1, vol. 46, pt. 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1894), 552. ↩︎

- New York State Archives, Cultural Education Center, Albany, New York; New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts, 1861-1900; Archive Collection #: 13775-83; Box #: 891; Roll #: 547, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025). ↩︎

- 1870 U.S. Census, Agricultural Schedule, Town of Champlain, Clinton County, New York, Page: 6; Line: 31, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025). ↩︎

- See Steven Ruggles, Prolonged Connections: The Rise of the Extended Family in Nineteenth-Century England and America (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987) for more information on the role of families in caring for aging relatives. ↩︎

- The Plattsburgh Sentinel, “Perry’s Mills,” December 24, 1875, 3. Plattsburgh Republican, “Proceedings of the Board of Supervisors – 1878,” February 1, 1879, 4. Plattsburgh Republican, “Town Accounts,” January 17, 1880, 4. ↩︎

- Plattsburgh Republican, “Town Accounts,” December 27, 1873, 2. ↩︎

- The Plattsburgh Sentinel, “Receipts for the Plattsburgh Sentinel,” December 15, 1876, 3. ↩︎

- 1880 U.S. Census, Agricultural Schedule, Town of Champlain, Clinton County, New York. p. 19, record 8, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025). ↩︎

- For more information on the transitions women made in the post-war period, see Tamara K. Hareven, Family Time and Industrial Time: The Relationship between the Family and Work in a New England Industrial Community (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1982). ↩︎

- U.S. Pension Application for Eli Carto, mother Salome Carto, filed June 6, 1894, Application No. 596623, Certificate No. 726671, New York; U.S., Civil War Pension Index: General Index to Pension Files, 1861–1934; Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, 1773–2007, Record Group 15; National Archives, Washington, D.C., Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025). ↩︎

- Plattsburgh Daily Press, “Perrys Mills,” September 23, 1897, 4. The Plattsburgh Sentinel, “Perry’s Mills,” December 3, 1897, 8. Cardinal Points, “Agenda Items,” January 1, 1898, 1. ↩︎

- 1900 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, page 25, family 362, Salame Carto household; digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing FHL microfilm: 1241018. ↩︎

- Plattsburgh Republican, “Wedding at Perrys Mills,” March 21, 1903, 1. ↩︎

Just curious, Darren–do any of the Carto’s progeny still live in the area of Perry’s Mills?

Wonderful stuff!

LikeLike