Oliver Lafontaine’s grave in Old Saint Mary’s Cemetery, Champlain, NY

Source: Find A Grave

If you walk the quiet rows of Champlain’s Old St. Mary’s Cemetery atop Prospect Hill, the wind slips unhindered through old stones softened by time. Among the stones lies the grave of Oliver Lafontaine.1 Oliver’s is a substantial monument—confident in its presence, firmly set, and deeply carved. Across its face stands the name LAFONTAINE, and beneath it the proud inscription, “Sgt. Co. H. 60. Rgt. N.Y.V. Inf.” Before one even sees the dates, the stone declares what mattered most: he was once a soldier.2 That identity, formed in the smoke, hunger, cold, and fear of the Civil War, shaped the long decades of life that followed, and it is the truest doorway into understanding the man buried beneath the Champlain earth.

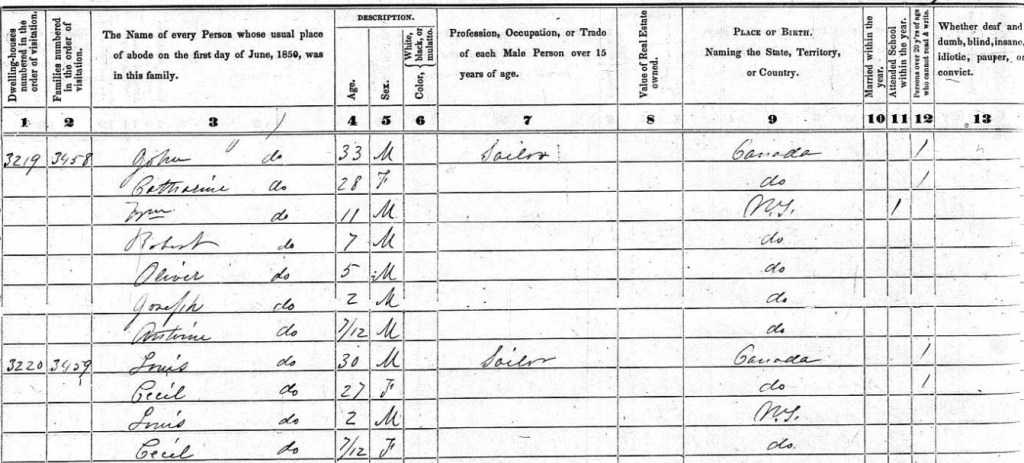

Oliver was born in Champlain on June 17, 1844, into a household tied to the movement of water and the rhythms of the lake. His father, John Lafontaine, had come from Canada and worked as a sailor on Lake Champlain, appearing in mid-century records as a boatman—a trade that required strength, stamina, and the willingness to live by the demands of wind, weather, and commerce. His mother, Catherine Roberts, kept the household anchored as children arrived one after another: William and John first, then Oliver, then Joseph, and finally an infant, Antoine, who appeared in the 1850 census. The Lafontaines lived among a French-speaking, cross-border culture that gave northern Clinton County its distinctive character—Catholic parishes, seasonal migration, mixed households of Canadian and New York birth, and economic life tied to farms, lake’s channels, and distant cities. This quality was underscored by their neighbor, Louis Lafontaine–John’s Canadian-born brother and also a sailor.3

The Lafontaine family in 1850

Source: 1850 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township.

Loss was woven into the early years for the Lafontaine family. Baby Antoine died in 1851; a daughter, Marie, born the same year as Antoine’s passing, also died in 1853. Such tragedies were common in the mid 19th century—cholera infantum, scarlet fever, dysentery, and pneumonia took young lives with stunning speed—but their emotional effects were intimate, reshaping families from within. Children grew up with the memory of siblings who did not survive; parents held grief while continuing to work and raise those who remained. Despite the loss, life marched on.

By 1860, sixteen-year-old Oliver lived in a home led by John, a boatman on the lake. The lake shaped the family’s work rhythms, diet, household, and social networks in ways that set them apart from the largely farming families of the area. The Lafontaines possessed no real or personal wealth in the census, suggesting they hovered economically between stability and precarity.4 John’s work on the lake would have been subject to the weather in an area where winters were long and income could evaporate with ice. In such circumstances, the regional economy produced young men accustomed to uncertainty and therefore unusually prepared for the decision that confronted them in 1861.

When the Civil War erupted in the spring of 1861, it was eldest son William who enlisted first on September 21, 1861 when he joined Company H of the 60th New York Infantry, a regiment forming at Ogdensburg with companies drawn from northern counties stretching from Malone to Champlain.5 The company reflected the social world the Lafontaine boys knew intimately: Champlain, Mooers, Ellenburgh, Altona, Chazy, and nearby towns were represented heavily in its ranks.6 One did not march into war among strangers but among neighbors, cousins, coworkers, the sons of parish families, and French Canadian migrants of a shared world.7

Oliver, only seventeen, watched William prepare to leave and refused to be left behind. Within a month—on October 21, 1861—he joined his brother in the very same company.8 Their names appeared together in enrollment tables and would remain paired in pay records, muster rolls, and casualty reports for years to come. In Champlain, their simultaneous enlistment confirmed what military historians repeatedly observe: that early-war volunteering often flowed through familial and neighborhood networks. The actions of the Lafontaine brothers reflected the patterns that defined Union enlistment culture as a whole during the early war.

The brothers and their comrades left New York on November 4, 1861, and spent the winter guarding the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad between Baltimore and Washington.9 For two young men raised in the rural borderlands of northern New York, army camp life must have been both thrilling and unsettling. Their introduction to military service was harsh: a measles outbreak in December 1861 afflicted more than 100 men.10

Although the boys wouldn’t have written to their parents (who reported on the census that they could not read or write), we know that the connection between the war front and home remained strong. The February 15, 1862 edition of the Plattsburgh Republican reported nine Champlain soldiers from Company H sending money home to their families; among those listed was Oliver sending $15 and William sending $8.11 That small line, nestled among the names of neighbors, captures the fluid duality of early service: boys gone to war, yet still part of the household economy; absent, yet still helping their family.

Illness in August 1862 left only a handful of officers to command Oliver’s regiment

Source: O’Sullivan, Timothy H, photographer. Fauquier Sulphur Springs, Virginia. Officers of the 60th New York Volunteers. United States, 1862. Aug. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2018671756/.

Their war changed quickly in the spring of 1862 when the regiment moved into the Shenandoah Valley under General Frémont and faced several probing Confederate detachments. Recalled to Pope’s Army of Virginia soon after, they found themselves confronted not only by maneuver warfare but by renewed sickness. By late July, a surge of typhus fever had sickened 140 men of the 60th New York. In early August, the regiment was sent to Fauquier White Sulphur Springs in hopes that its mineral waters might restore the sick. By August 15, the regimental surgeon reported 350 men battling typhus indoors and another 50–60 confined to tents with lesser symptoms.12 We do not know whether Oliver or William fell ill, but the infection rate makes it likely they were either sick themselves or carrying the burdens of those who were.

By September the regiment was on the mend and joined the army that was confronting Robert E. Lee’s invasion of Maryland. At Antietam on September 17, 1862, Oliver and his comrades advanced with Greene’s division toward the West Woods, entering a landscape already choked with smoke and confusion. Crossing ground littered with the casualties of earlier fighting, they pushed into the woods where visibility dropped to yards and command structure quickly frayed. The regiment helped drive Confederate lines backward in the initial assault, but momentum came at a cost: they soon found themselves isolated, exposed to fire from multiple directions. When Confederate reinforcements struck the flank, the regiment’s colonel—commanding the brigade—fell mortally wounded and the 60th New York withdrew toward the main Union line, having lost nearly a third of the men it carried into the fight.13 For Oliver, it was likely a blur of shouted orders, rolling volleys, and the eerie disorientation veterans later described as the emotional core of Antietam.

Chancellorsville and Gettysburg in 1863 carried Oliver, William, and the 60th New York through two more of the war’s most disorienting campaigns, battles remembered today for their sweeping maneuvers but experienced by men like him only in fragments—shouts, smoke, and the sudden rush of orders that could reverse direction in an instant. At Chancellorsville in May 1863, Oliver would have marched into tangled woods alive with the constant crack of skirmish fire, where the undergrowth swallowed whole companies and visibility collapsed into a few yards of shifting silhouettes. He would not have known the larger plan, only that the fighting surged unpredictably, that the regiment took heavy losses, and that even seasoned officers seemed shaken by the ferocity of the Confederate assaults. By the time the battle was over, sixty-six more men in the 60th were casualties.14 Two months later at Gettysburg, the 60th was thrown onto the rocky, timbered slopes of Culp’s Hill—ground that offered protection only if held firmly and punished any faltering. For Oliver, the battle came as a long stretch of tense hours behind hastily built earthworks, punctuated by sudden eruptions of musketry when the enemy pushed through the trees. He would have heard the shouted commands to hold the line, the thump of artillery somewhere beyond the hill, and the eerie pauses when both sides lay low among the rocks, waiting for the next push. When daylight finally broke on July 3rd and the Confederate attacks faded, Oliver emerged from the trenches knowing only that his regiment had survived another trial and that fifty-five friends he had eaten, marched, and joked with were casualties.15 Whatever newspapers or historians later made of Chancellorsville’s brilliance or Gettysburg’s turning-point significance, Oliver’s memories would have likely been rooted in cramped quarters, dense woods, long night watches, and the sobering count of men like Champlain-native Philetus Ayers did not answer roll call the next morning.16

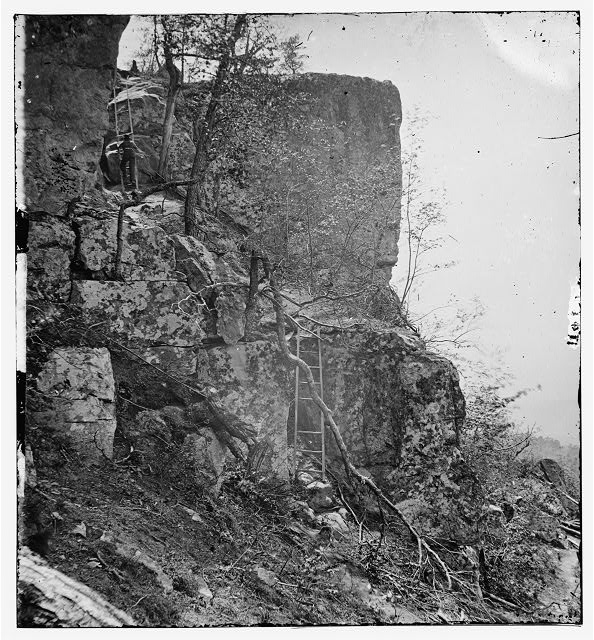

Oliver and the 60th underwent a change of scenery when the XII Corps was transferred west to support the Army of the Cumberland. They fought at Wauhatchie and then entered the Chattanooga Campaign, where the regiment’s role would place Oliver in the thick of his most defining moment. The “Battle Above the Clouds,” as newspapers and veterans called it, acquired a mythic character in postwar memory, but for the men on the slopes that day, it was anything but romantic. It began in darkness, before dawn on November 24, 1863, when the 60th New York received orders to fall in with one day’s rations, no knapsacks, no blankets, and to move towards ascending a looming mass of a mountain deemed as “impregnable.”17

The challenging terrain on Lookout Mountain tackled by Oliver in November 1863

Source: Chattanooga, Tenn., vicinity. Summit of Lookout Mountain. Chattanooga Tennessee United States, 1864. [?] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2018666961/.

The air thickened with fog as they marched toward Lookout Creek. They crossed in dim morning light, boots slipping on slick stones, the sound of the current swallowed by mist. Once across, the ascent began immediately. The terrain was punishing—dense spruce undergrowth, fallen timber, and jagged boulders forced the regiment upward in a staggered, straining line. At times they scrambled; at others they pulled themselves upward hand over hand, the mountain seeming almost to resist their passage. Hours into the climb, skirmish fire crackled in the fog as Confederate pickets were encountered. The regiment halted only briefly before orders came to press on. Then, in the moment preserved in the 60th’s regimental history, they fixed bayonets and surged forward “with a shout such as only Yankees can give,” overrunning an unfinished Confederate earthwork before defenders could mount an organized stand. By early afternoon, Oliver and the 60th had climbed nearly three miles and secured their objective.18

The toll of the ascent became clear only when the firing ceased. One Champlain man, George Mayo, was killed; two others—Alexander Hubbell and Sidney Rider—were wounded.19 Though not recorded in the regimental narrative, Oliver later reported that he, too, was wounded at Lookout Mountain, a detail preserved only in terse military records. The circumstances of his injury—like so many battlefield wounds—were lost to the larger chaos of the campaign. Yet what is known matters: despite the wound, the cold, and the months of relentless marching, he reenlisted on December 11, 1863, as a veteran volunteer.20 His decision mirrors patterns noted by historians of reenlistment: hardened identity, loyalty to comrades, community expectations, and the economic realities facing working-class northern men.21

The regiment received veteran furlough in the winter and then returned to the field in early 1864 as part of Sherman’s XX Corps. William and Oliver marched together once more through that spring and summer, advancing through the Atlanta Campaign—Resaca, New Hope Church, Peachtree Creek—battles marked by maneuver, heat, constant skirmishing, and attrition.22 These were not the spectacular engagements of the Eastern Theater; they were grinding, methodical, and deadly. The brothers who had enlisted in 1861 were now seasoned veterans, intimately familiar with exhaustion, deprivation, and the tightening grip of the war’s final years.

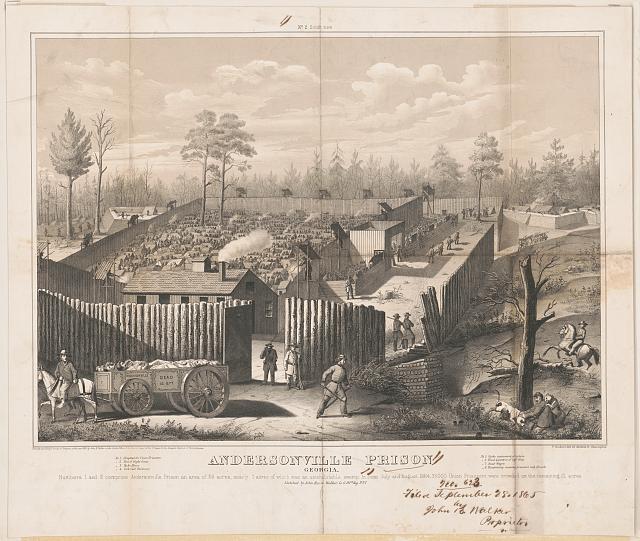

A lithograph showing the prison where William was sent in 1864

Source: T. Sinclair’s Lith., Publisher, and John Burns Walker. Andersonville prison. Georgia / Sketched by John Burns Walker, Co. G, 41st Regt. P.V.I. Georgia Andersonville United States, ca. 1864. Phila.: T. Sinclair’s lith. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2003662359/.

In March 1864, the brothers’ paths diverged in a way neither could have predicted. William was captured and taken first to Andersonville, the most infamous prison of the Confederacy. There he endured starvation rations, disease, filth, exposure, and the daily sight of men dying around him. His survival was based on physical toughness and a stroke of luck. From Andersonville he was transferred to the prison at Florence, South Carolina, where conditions were scarcely better. The war had seized him in the most brutal way; when asked in 1866 to describe his experiences, William reported he “suffered all the tortures that starvation can give.”23

The war’s toll deepened for the Lafontaine family in 1864. First William disappeared into Confederate captivity, and then the conflict reached toward John, Oliver’s other older brother. John had enlisted in Company H of the 11th New York Cavalry in March 1862 and spent two years riding patrols around Washington, D.C., before the regiment was sent to the Department of the Gulf in the spring of 1864.24 The change of climate proved deadly. Disease coursed through the camps with a relentlessness the cavalry could not outrun, and by late autumn John—now a Quartermaster Sergeant—was sick enough to be ordered north to recover. He boarded the steamship North America in New Orleans with more than two hundred other convalescents bound for Washington. But on the night of December 22, off the coast of northern Florida, a violent gale rose out of the darkness. The new ship sprang a forward leak, and despite frantic efforts to save her, she foundered in the storm.25 Nearly two hundred soldiers drowned, John among them. For his family in Champlain, the loss arrived only as a distant notice—death without a body, grief without a grave, and yet another echo of the war’s reach into their household.

Recovered from the wound received at Lookout Mountain, Oliver continued with the 60th New York Infantry. He was promoted to corporal on September 10, 1864 shortly before the regiment marched with Sherman across Georgia. His youngest brother, Joseph, enlisted in early 1865, but was assigned duty on the Canadian border. Oliver, meanwhile, continued to face risks as the army marched north through the Carolinas to the final battles of the spring of 1865. When the 60th New York entered Washington for the Grand Review, Oliver was among the men who marched down Pennsylvania Avenue in the triumph of armies that had known more hardship than celebration. Shortly thereafter, Oliver was promoted sergeant on June 22, 1865, before being mustered out of the service on July 17, 1865.26

Oliver returned home to Champlain in 1865 carrying wounds, memories, and the invisible weight of one brother who had suffered and another who had never returned. In July 1866 he married Zoe Cardin, a Champlain native whose family, like many in the area, was tied to the French Canadian communities across the border.27 Their nine children arrived across the next two decades: Oliver Jr., Mary Agnes, Albert, John Baptiste, Guillaume, Augustus, Joseph Adelard, Zoa Alica, and Catherine.28 When the state census taker visited the family in 1892, Oliver and Zoe had a bustling household still filled with seven children.29 Eldest son Oliver had begun his own life by that point, and the family had already mourned the death of infant Guillaume in 1878. The early 1890s would prove difficult for the family, however, as they grappled with the death of both Joseph on December 16, 1893 and Zoa on February 24, 1895.30 Like so many other families, the rhythm of domestic life from the 1870s through 1900 swung between joyful events such as births and baptisms to challenges such as winter scarcity and funerals.

After the war, Oliver’s working life unfolded almost entirely on the water. The 1870 census captured him as a ‘Captain Lake Boat,’ and later enumerations alternately called him a sailor or boatman—labels that obscured the continuity of a decades-long career on Lake Champlain. He likely hauled numerous products and navigated a lake economy that depended on timing, skill, and annual cycles of freeze and thaw. The 1892 census offers a glimpse of his community: six neighbors worked as boatbuilders, and his cousin Louis served as a pilot, forming a small maritime world tied to the lake’s seasonal demands. By 1900, Oliver reported five months of unemployment—almost certainly the winter freeze that halted navigation entirely—an annual rhythm familiar to Champlain boatmen across generations.31

The opening years of the twentieth century brought a cascade of losses to Oliver and Zoe. His father John’s death in 1902 marked the first rupture, followed by the passing of Oliver’s mother, Catherine, in February 1906.32 That fall, another blow struck the family when their eldest daughter, Mary Agnes, died at just thirty-six, leaving seven young children motherless with the youngest, Florence, just weeks old when Mary passed. These bereavements accumulated, shaping a period in which private grief repeatedly unsettled the household.33 Then, in 1910, Oliver confronted a loss that reached back into the defining experiences of his youth. William—his eldest brother and comrade in the 60th New York Infantry—died in May. The local newspaper emphasized both William’s war-time ordeal and the enduring ties among the brothers:

“Wm. Lafontaine… languished for several months in the Andersonville prison and his health had been so impaired that he could never have reached home at the close of the war without the assistance of the late Louis Brassard… The latter [Oliver] left here Friday morning to visit his brother in his last illness, but found him dead upon reaching Springfield.”34

More than four decades after the war, memories of William’s suffering in Andersonville remained vivid in the community’s memory. For Oliver, those memories were not abstract history but lived experience as the bonds forged in childhood and reaffirmed in the crucible of battle still held. Even in his mid-sixties, he made the long journey to Springfield, MA hoping to see his brother one last time.

The same year of William’s death saw the census taken once more visit the Lafontaine family. A decade earlier, Oliver and Zoe were listed as renters, but now they could report that they owned their home free of mortgage, anchoring them more firmly than ever in the community that had shaped their entire lives. When asked about his Civil War service, Oliver did not hesitate—he told the enumerator that he had served in the Union Army, a quiet affirmation that the defining experience of his youth still mattered in his old age. The census also revealed how deeply the Lafontaine commitment to family endured. Oliver and Zoe were sharing their home with their son Augustus and their daughter Catherine, and under their roof was a final reminder of Mary’s too-short life: little Florence, their “adopted daughter,” only three years old, whom they were raising after Mary’s death in childbirth.35

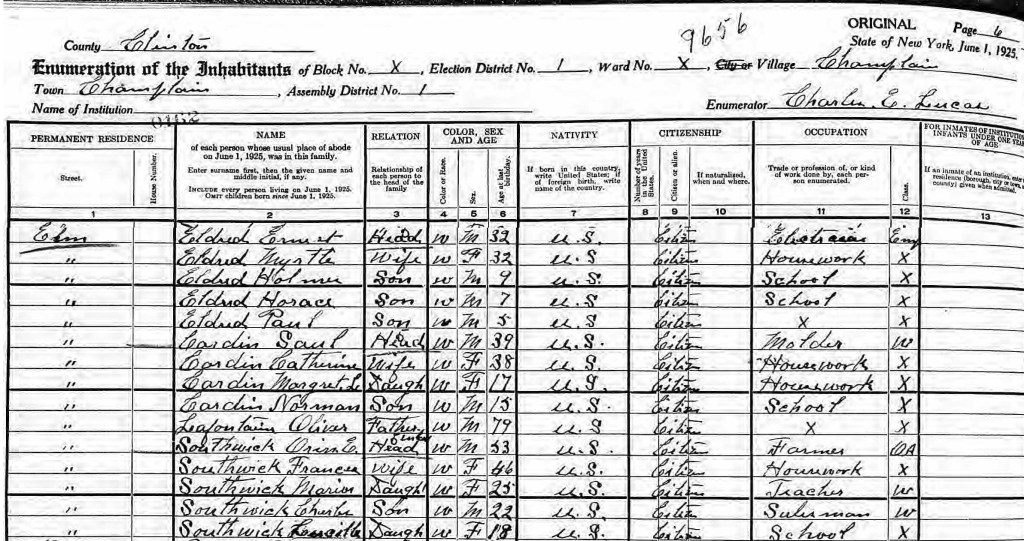

Oliver’s last appearance in any census

Source: 1925 New York State census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township.

Before the next census visit, Oliver would have to absorb loss once more–this time it was his wife of more than fifty years, Zoe.36 In his final appearance in a census, the widowed Oliver is found living on Elm Street in the village with his youngest daughter Catherine and her growing family, an elderly veteran carried into his final years by the long continuity of kin networks that defined French Canadian families in the region.37

Oliver died on July 5, 1928, at the age of eighty-four, one of the last remaining Civil War veterans in Champlain. By then the world that had formed him was fading. The wooden schooners on the lake were disappearing; the French-speaking population of Champlain was shifting; the veterans’ parades were thinning each year. But his stone at St. Mary’s remained—and remains—firm, unweathered in its essential lines, declaring his name and his service. “Sgt. Co. H. 60. Rgt. N.Y.V. Inf.” It is not simply a summary; it is a summation of a life in which the Civil War was the crucible, the defining fire through which everything else passed.38

Endnotes

- For consistency across this tale, I have opted to use the Lafontaine family name. Various records will show the name as Lafountain, Lafountaine, and other variations. I have made the same decision for first names; for example, Oliver’s father is sometimes seen as the following: John, Jean, Jean-Baptiste.

- Find a Grave, memorial page for Oliver LaFontaine (1829–1915), Memorial ID 96892265, citing Old Saint Mary’s Cemetery, Champlain, Clinton County, New York; accessed December 6, 2025.

- 1850 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, John Lafontaine household, dwelling 3219 family 3458, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll 490, Page: 477b.

- 1860 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, John Lafontaine household, dwelling 885 family 933, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll 653_736, Page: 698.

- William Lafountain, Champlain Town Clerks’ Registers of Men Who Served in the Civil War, ca. 1861–1865, Collection (N-Ar)13774, Box 12, Roll 8, New York State Archives, Albany.

- New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs Museum, “60th Regiment Infantry Civil War Roster,” PDF, accessed December 6, 2025, https://museum.dmna.ny.gov/application/files/7315/5068/2210/60th_Infantry_CW_Roster.pdf.

- For more information on motivations of early Civil War volunteers, see Reid Mitchell, The Vacant Chair: The Northern Soldier Leaves Home (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), esp. pp. 44–52 on motivations of working-class enlistees; Maris A. Vinovskis, “Have Social Historians Lost the Civil War? Some Preliminary Demographic Speculations,” in Toward a Social History of the American Civil War: Exploratory Essays, ed. Vinovskis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 6–12.

- Oliver Lafountain, Champlain Town Clerks’ Registers of Men Who Served in the Civil War, ca. 1861–1865, Collection (N-Ar)13774, Box 12, Roll 8, New York State Archives, Albany.

- Richard Eddy, History of the Sixtieth Regiment New York State Volunteers, from the Commencement of Its Organization to the Close of the Civil War (Philadelphia: D. O. Haynes & Co., 1864), 46-72, https://archive.org/details/historyofsixtiet00eddy/page/360/mode/2up.

- Ibid., 65 and 142.

- Plattsburgh Republican, February 15, 1862, 2.

- Eddy, History of the Sixtieth Regiment, 142, 158.

- Ibid., 172-182.

- Ibid., 243-246.

- Ibid., 259-264.

- Ibid., 278.

- Ibid., 305.

- Ibid., 306-308.

- Ibid., 309.

- Oliver Lafountain, Champlain Town Clerks’ Registers of Men Who Served in the Civil War, ca. 1861–1865, Collection (N-Ar)13774, Box 12, Roll 8, New York State Archives, Albany.

- See Mitchell, The Vacant Chair; Vinovskis, “Have Social Historians Lost the Civil War?” for more information on reenlistment influences and demographic constraints among veteran volunteers.

- Frederick Phisterer, New York in the War of the Rebellion, 3rd ed. (Albany: J. B. Lyon Company, 1912), 1:306–7.

- William Lafountain, Champlain Town Clerks’ Registers of Men Who Served in the Civil War, ca. 1861–1865, Collection (N-Ar)13774, Box 12, Roll 8, New York State Archives, Albany.

- John Lafountain, Champlain Town Clerks’ Registers of Men Who Served in the Civil War, ca. 1861–1865, Collection (N-Ar)13774, Box 12, Roll 8, New York State Archives, Albany.

- New York Times, January 24, 1865, reprinting an article from the New-Orleans Times, January 12, 1865; quoted in “1864 — Dec 22, U.S. Steam transport North America sinks,” Deadliest American Disasters and Large-Loss-of-Life Events, accessed December 4, 2025, https://www.usdeadlyevents.com/1864-dec-22-u-s-steam-transport-north-america-sinks-storm-off-coast-of-north-fl-197/.

- Oliver Lafountain, Champlain Town Clerks’ Registers of Men Who Served in the Civil War, ca. 1861–1865, Collection (N-Ar)13774, Box 12, Roll 8, New York State Archives, Albany. Joseph Lafountain, Champlain Town Clerks’ Registers of Men Who Served in the Civil War, ca. 1861–1865, Collection (N-Ar)13774, Box 12, Roll 8, New York State Archives, Albany.

- 1900 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Oliver Lafontaine household, dwelling 152 family 152, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll 1018, Page: 11.

- 1870 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Oliver Lafontaine household, dwelling 291 family 297, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll M593_918, Page: 172A. 1880 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Oliver Lafontaine household, dwelling 78 family 78, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll 819, Page: 153b.

- 1892 New York state census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Oliver Lafontaine household, page 14, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025).

- Find a Grave, memorial page for Oliver LaFontaine (1829–1915), Memorial ID 96892265, citing Old Saint Mary’s Cemetery, Champlain, Clinton County, New York; accessed December 6, 2025.

- 1870 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Oliver Lafontaine household, dwelling 291 family 297, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll M593_918, Page: 172A. 1880 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Oliver Lafontaine household, dwelling 78 family 78, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll 819, Page: 153b. 1900 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Oliver Lafontaine household, dwelling 152 family 152, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll 1018, Page: 11.

- New York State Department of Health, “John B. Lafountain death entry, 1902,” New York State Death Index, 1880–1956, Ancestry.com, citing Certificate Number 12928; accessed December 7, 2025. New York State Department of Health, “Catherine Lafountain death entry, 1906,” New York State Death Index, 1880–1956, Ancestry.com, citing Certificate Number 8261; accessed December 7, 2025.

- 1905 New York state census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Napoleon Babeau household, page 20, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025). New York State Department of Health, “Agnes Babaw death entry, 1906,” New York State Death Index, 1880–1956, Ancestry.com, citing Certificate Number 48989; accessed December 7, 2025.

- “Budget of Champlain News,” The Plattsburgh Sentinel, May 13, 1910, 2, col. 3.

- 1910 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Oliver Lafontaine household, dwelling 199 family 204, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll T624_932, Page: 16b.

- New York State Department of Health, “Zoe Lafontaine death entry, 1919,” New York State Death Index, 1880–1956, Ancestry.com, citing Certificate Number 32762; accessed December 7, 2025.

- 1925 New York state census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Saul Cardin household, page 6, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025).

- Find a Grave, memorial page for Oliver LaFontaine (1829–1915), Memorial ID 96892265, citing Old Saint Mary’s Cemetery, Champlain, Clinton County, New York; accessed December 6, 2025.