George and Edith Phaneuf’s grave in Saint Ann’s Cemetery, Mooers Forks, NY

Source: author’s personal collection

Along a row near the property line of Saint Ann’s Cemetery in Mooers Forks, New York, a modest gravestone marks the resting place of George Edward Phaneuf. The marker offers little beyond his name, dates, and the promise of “Perpetual Care.”1 There are no carved tools to suggest a trade, no epitaph to summarize a life. Yet the stone marks the end of a life that unfolded almost entirely within sight of a water-powered sawmill in Perry’s Mills—a life shaped early by loss, sustained by physical labor, and marked by a resilience forged long before adulthood.

George was born on Christmas Day, 1892, in the small hamlet of Perry’s Mills, part of the town of Champlain, New York, a border town whose rhythms were set by agriculture, timber, and the steady movement of goods and people across the Canadian line.2 Champlain’s history had long been shaped by larger forces. Founded after the American Revolution, it endured British incursions during the War of 1812, benefited from nineteenth-century railroad expansion, and depended on the Great Chazy River to power mills that anchored local employment. By the time of George’s birth, Champlain had become a modest industrial-agricultural community linked to Montreal and the Hudson Valley by rail.

George’s parents, Antoine Phaneuf and Laura Roy, were part of the region’s substantial French-Canadian Catholic population.3 Antoine, thirty-seven at the time of George’s birth, was born in Champlain after his family immigrated from Canada in the 1840s to work in the lumber industry.4 Laura, twenty-seven at George’s birth, was also born in New York, likewise the daughter of two French-Canadian immigrants. Her childhood was marked early by loss. At the age of four, Laura’s mother died, forcing an abrupt reorganization of family life. The 1870 census records the family headed by her father, Bozil Roy, assisted by a French-Canadian housekeeper, Mary Lafountain. Even in childhood, economic necessity shaped family life. Laura’s three older brothers—Mitchell, age nineteen; Bozil, sixteen; and Felix, eleven—were already employed in a local shingle mill, a pattern common in wage-earning households of the period.5

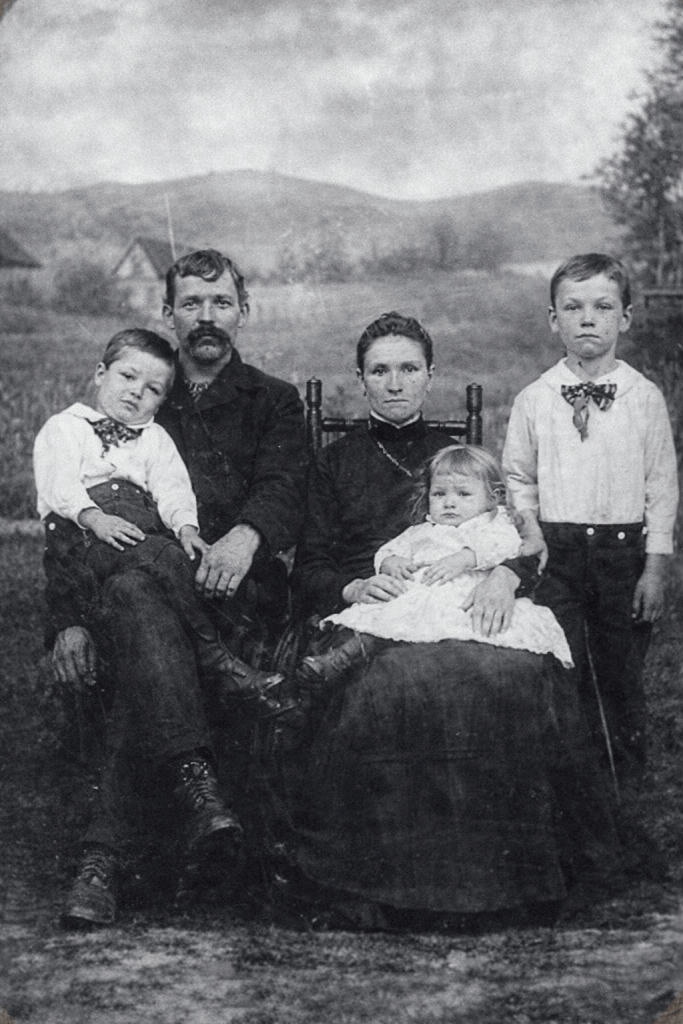

Antoine and Laura with their first three children: Frank, Laura, and Antoine (l-r)

Source: author’s personal collection

Within a decade of losing her mother, Laura married Antoine at the age of fifteen and began a family of her own, entering a household already shaped by necessity rather than choice. Despite being newly married, Antoine and Laura’s household already reflected the complexity common to families of the period—blended kin networks shaped by loss, necessity, and shared work. Laura’s aging father continued to live with them, as did her brother Felix, reinforcing the interdependence of extended family members.6 Over the next several years, their household expanded with the births of children Antoine, Frank, and Laura; after George’s birth in 1892, daughters Hattie and Dora also joined the family.7 George’s early childhood unfolded within a recognizable late-nineteenth-century rhythm of family life—routine, labor, faith, and the quiet expectation that survival was collective.

George’s childhood was abruptly altered in April 1898, when his mother Laura died at age thirty-three.8 Her death echoed an earlier family trauma—Laura herself had lost her mother in 1869—and in an era without social welfare systems, such a loss was not merely emotional but structurally destabilizing. Working-class mothers coordinated the essential labor of daily survival, from food preservation and clothing production to childcare, illness management, and emotional regulation, all without the benefit of antibiotics or public assistance. Their absence forced families to reorganize quickly and children to assume adult responsibilities with little transition. Historians of childhood bereavement suggest that early parental loss often produced not rebellion, but inward discipline: a quiet orientation toward reliability, repetition, and obligation.9 For George, the lesson learned in childhood was not how to escape hardship, but how to endure it. That pattern would repeat throughout his life.

George’s first appearance in the census, at age seven, records him living in Champlain under one of several phonetic spellings—Fenneff, Phenuff, Pheneuf, and Phinnff—that recur throughout the historical record. Such distortions were common for French surnames recorded by English-speaking census takers; names bent easily under the pen, even as the expectations attached to those names remained fixed. The census places George in a crowded, multigenerational household with his father and stepmother Mary, alongside five siblings, two stepbrothers, and two additional stepsisters, the byproduct of losing his mother.10

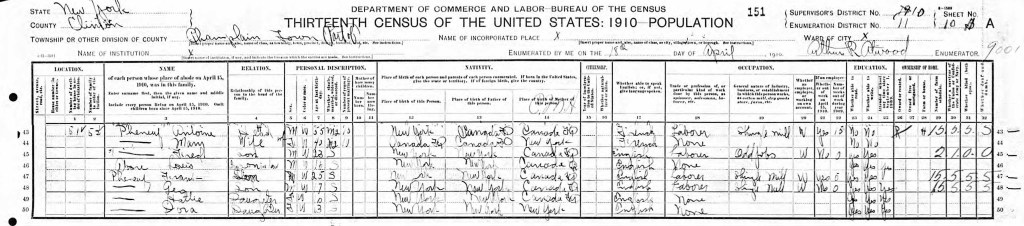

George and his blended family in 1910–although just 17, he’s already working full-time

Source: 1910 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township.

By 1910, seventeen-year-old George was already employed as a laborer at a shingle mill, having left school early—a common path for rural working-class youth—for full-time wage labor. His blended household, still led by his father Antoine and stepmother Mary, depended on multiple wage earners to remain afloat. At the time of the census taker’s visit, two adult males in the household were unemployed—Antoine for fifteen weeks and George’s brother Frank for five—leaving only George and his stepbrother Fred contributing wages.11 George’s work, however, was anything but easy. Lumber and sawmill labor in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was widely recognized as physically punishing and dangerous. Millworkers operated exposed blades, belts, and water-powered machinery in poorly lit buildings, often at high speeds and with little protection. Safety regulations were minimal, and injuries—from amputations to fatal crushing accidents—were accepted as occupational hazards rather than aberrations. Early industrial lumber workplaces were among the most dangerous in the American economy, with injury and fatality rates that far exceeded those of many other industries.12 For George, this environment was not exceptional but formative: a world in which danger became routine and physical endurance replaced formal education as the foundation of his adult identity.

Champlain itself was changing as George came of age, though unevenly and often incompletely. Horses still dominated transportation, but automobiles began appearing on village roads before World War I. Electricity reached some households, yet access remained inconsistent and often bypassed renters and laborers. New industries briefly flourished, including ski manufacturing launched by Swedish immigrants Oscar and Henrik Bredenberg, whose workshop—and later factory—placed Champlain at the forefront of an emerging sport.13 Novelty industries rose and fell, yet timber endured, bound to the land, the river, and the unchanging need for shelter.

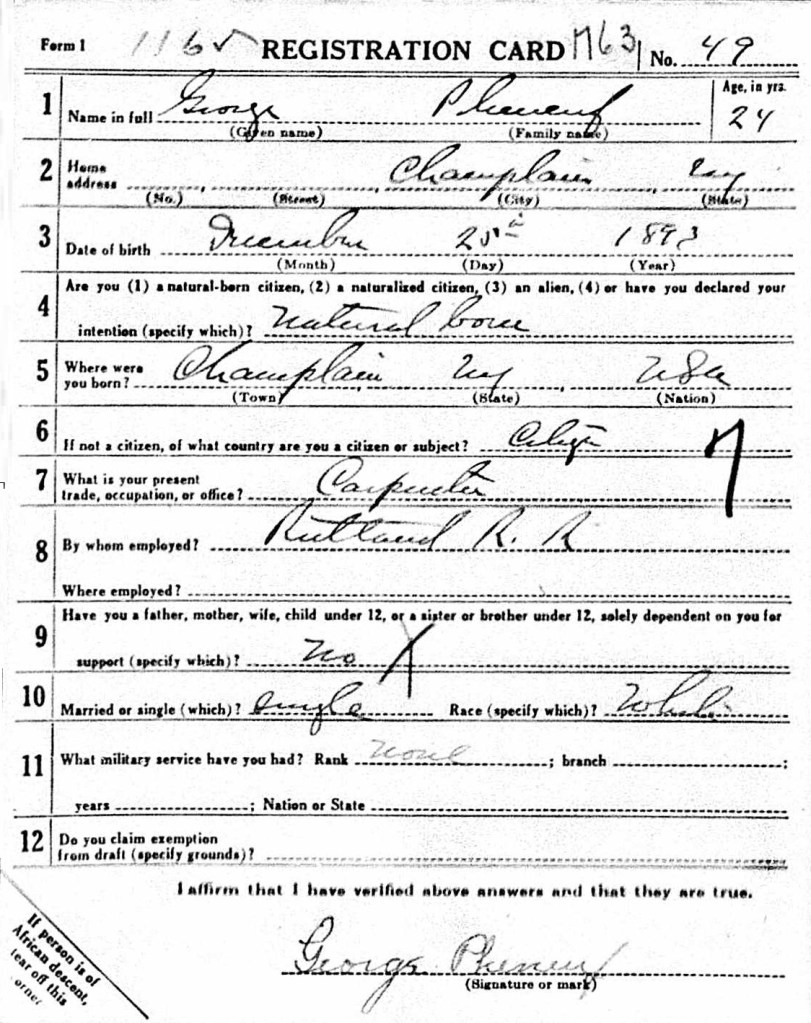

George’s WWI draft registration showing both his work for the Rutland RR and his signature

Source: U.S. World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918

In June 1917, as the United States entered World War I, George registered for the draft, described in his registration as brown-haired and brown-eyed, and listing his occupation as carpenter employed by Hector Kaufman of Perry’s Mills—the small hamlet west of Champlain where he had been born and raised.14 This was part of a lifelong association with the Kaufman Lumber Company, a water-powered sawmill that served as the economic anchor of Perry’s Mills for generations. Operating continuously since the early 1900s, the Kaufman Lumber Company was old-fashioned even by early twentieth-century standards. Powered by water flowing beneath its floor, it belonged to a dwindling class of mills that relied on natural force rather than steam or electricity. The mill employed between six and twelve men depending on the season. Logs—primarily pine and hemlock—were purchased, sawn, planed, and sold as building materials to surrounding farms and towns. A planing mill operated alongside the sawmill, and the company supplied lumber essential to barns, houses, and fences throughout the region.15 At a moment when millions of young men were uprooted and sent across oceans, George remained rooted to the local economy, producing the materials that undergirded both civilian life and wartime mobilization.

The war years brought steady demand for lumber, even for men who never went overseas. On September 1st, 1919, George married Edith Meseck, nine years younger, from nearby Mooers Forks.16 Echoing another trend among French Canadians of the era, George married the sister-in-law of his younger sister Hattie, who had married Edward Meseck in April 1911. The marriage of George and Edith didn’t immediately find them residing on their own–the 1920 census records the newlyweds living with George’s father Antoine and his brother Frank in Perry’s Mills, just across the river from the lumber mill, anchoring home and work in the same physical landscape.17

The 1920s did not roar in Perry’s Mills. For working families, prosperity meant steady employment rather than consumer abundance. George’s wages covered food, rent, and clothing as the family expanded, beginning with the birth of Floyd in 1920; by 1930, George and Edith were raising five children.18 The family likely moved between rented homes near the mill, minimizing transportation costs and keeping George within walking distance of work. For him, employment at Kaufman’s offered routine rather than advancement. He performed physically demanding labor year after year, adapting to seasonal rhythms dictated by water and weather: winter froze the stream beneath the mill floor, spring thaws brought dangerous surges, and summer demanded long hours. The work required sustained attention, strength, and an acceptance of risk. Men aged quickly in such environments, their bodies absorbing the cost of constancy.

The Great Depression arrived not as a single event but as a tightening vise that transformed subsistence into struggle. Construction slowed, credit vanished, and seasonal layoffs lengthened, hitting rural northern New York especially hard as collapsing farm prices and stalled building projects reduced demand for lumber.18 George remained employed at Kaufman Lumber, working long hours for modest wages while renting a small home in Perry’s Mills, just a few houses from mill owner Hector Kaufman. The survival of the household, however, depended as much on Edith’s labor as on George’s wages. Edith managed the family economy with skill and discipline, stretching every dollar through production rather than purchase. The family planted large gardens each spring, tended crops through the short growing season, and preserved the harvest in the fall, canning tomatoes, string beans, beets, and other vegetables to sustain the household through the long North Country winters.

As the 1930s progressed, Edith’s responsibilities expanded alongside the household itself, which grew from five children to ten over the course of the decade.20 Each additional birth increased the demands on a system already stretched thin. Pregnancy, childcare, illness, and food management overlapped continuously, leaving little margin for rest or error. Older children were drawn early into household labor, caring for younger siblings, assisting with food production, and contributing in ways that blurred the line between childhood and work. The family functioned as an interdependent unit, its internal cooperation mirroring the collective labor required in the mill where George spent his days. While George’s family expanded, his father Antoine died at eighty-three in 1938, closing the generational arc that had shaped George’s childhood.

The one known photo of George and Edith, circa 1965

Source: author’s personal collection

The 1940 census illuminates how George sustained a household of twelve ranging in age from twenty-year-old Floyd to newborn Jean. George continued to work forty-eight hours per week at the lumber mill and had been employed for all fifty-two weeks of the previous year, earning $936—about $18 per week, or thirty-seven cents an hour—an income that made providing for such a large family a constant challenge. Survival depended on shared labor. George’s eldest son, Floyd, worked thirty-five weeks at the mill, contributing $372 to the household economy, while eldest daughter Lorena earned an additional $15 through part-time domestic work.21 Younger children packed shingles with George in the evenings for piece-rate wages, and the family supplemented income further by harvesting potatoes for the local general store. The family’s ability to remain employed and assemble multiple income streams through the Depression speaks not to prosperity, but to reliability. George showed up. He worked. He endured.

World War II brought renewed demand for lumber and new anxieties at home. While George continued working, producing materials essential to a global conflict, Floyd enlisted in the U.S. Army on February 8, 1944, in Albany, New York.22 Entering service as a private, he was sent to the Pacific Theater, where American forces faced brutal jungle warfare, disease, and staggering casualty rates.23 For George and Edith, Floyd’s service meant prolonged uncertainty. Letters arrived sporadically. Newspapers carried casualty lists. As a father who had labored through the Great Depression and witnessed one world war already, George understood the particular burden war placed on laboring families. Survival was never assumed. That Floyd returned alive was itself a victory marked quietly, without ceremony.

While war intensified risks abroad, George himself faced dangers of a different sort in his day-to-day work. Nowhere was that made more clear than when in December 1946, Hector Kaufman Jr., George’s employer and fellow laborer, was caught in a revolving shaft while attempting to slip a belt onto a pulley. His clothing was torn from his body. His right leg required amputation; his left leg, both arms, and ribs were broken; his lung punctured. As the machinery continued to turn, workers rushed to intervene. Among them were Frank Phaneuf, George’s brother, and Cyrus Baker, George’s brother-in-law, married to his sister Laura. Together, they slowed the water-powered machinery long enough for Kaufman to drop free into the pit beneath the mill floor. Their actions almost certainly saved his life.24 The accident underscored the daily risks George accepted as routine, hazards endured quietly in exchange for wages and continuity, while also highlighting how labor and kinship overlapped. Men did not merely work alongside relatives—they relied on them for survival.

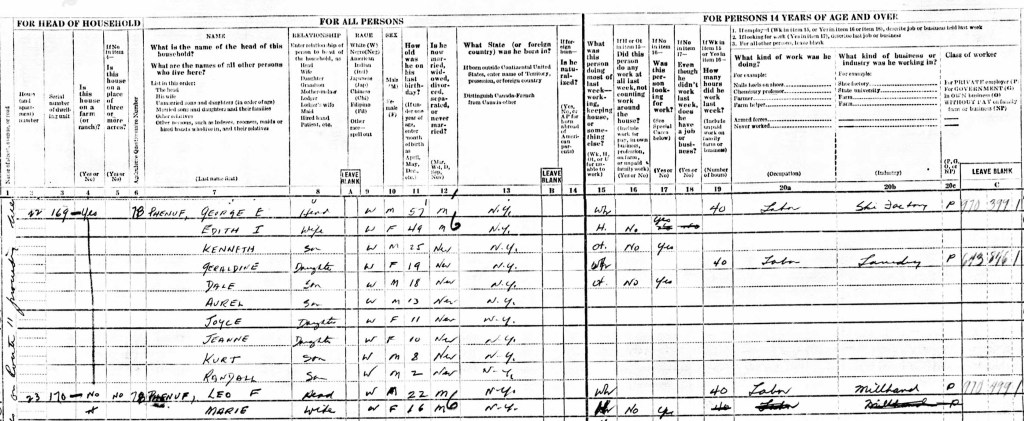

George and his family in 1950–he lives with seven kids and one grandchild on Mill Street; son Leo and wife Marie live next door

Source: 1950 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township.

By 1950, the household George and Edith Phaneuf sustained remained complex rather than diminished. Ten people spanning three generations lived together on Mill Street in Perry’s Mills, where the youngest son, Kurt, was only six years older than his nephew Randall. At fifty-seven, George was still working full-time, now employed at the Bredenberg Brothers Ski Factory on Butternut Street in the village of Champlain—a reminder that industrial labor, rather than retirement, defined middle age for working-class men. The household economy depended on multiple contributors: daughter Geraldine worked full-time at a local laundry, while two older sons were actively seeking employment.25 Edith’s labor remained central. Routine chores such as laundry required hauling water from the river by wheelbarrow to fill the family’s gasoline-powered ringer washing machine, a vivid measure of the physical demands that persisted in daily life well into the postwar era.

Life in the Phaneuf household was not defined solely by work, loss, or economic strain. Music played a central role in family life, providing both pleasure and connection. Several of the children learned instruments, and the family regularly transformed their home on Mill Street into a social space. Furniture was pushed aside, the main floor cleared, and relatives and neighbors gathered for evenings of music and dancing. These gatherings offered a release from the routines of labor and responsibility and reinforced bonds of kinship and community. That love of music endured across generations. In later years, obituaries for two of George’s sons recalled lives shaped not only by work and family but by performance, noting their involvement in regional bands such as Chick O’Day and the Country Cousins and Tequila. Music, like labor, became a thread of continuity—something carried forward, adapted, and shared—offering balance to lives otherwise governed by obligation.26

Music offered moments of release and connection, but it could not insulate the Phaneufs from grief. Loss continued to shape George’s life beyond the workplace and beyond the moments of shared joy that filled their home. In March 1947, George’s oldest sister Laura died in Champlain at the age of forty-nine after a long illness, further thinning the family network that had sustained him since childhood.27 Obligations endured even as familiar anchors disappeared.

Loss returned with particular force in February 1956, when Lorena, George and Edith’s eldest daughter, died unexpectedly at the Montreal Neurological Institute after suffering a brain aneurysm at the age of thirty-three.28 She was buried in Saint Ann’s Cemetery in Mooers Forks, her gravestone bearing the inscription: “If tears could build a stairway and memories build a lane, I’d walk right up to heaven and bring you home again.” For George, Lorena’s death echoed the loss of his mother decades earlier, reinforcing grief as a recurring presence woven through life rather than a single, defining rupture.

Firefighters battling the fire at the Mill Street, Perry’s Mills, NY home in 1962

Source: courtesy of Donald Phaneuf

By the 1960s, George and Edith were aging, and the losses that had long punctuated their lives began to arrive with increasing frequency. Over a span of just four years, Edith lost five siblings, including her brother Eddie, who had been married to George’s sister Hattie and was likely the social connection through which she and George first came together. The year 1962 was particularly devastating for George. In February, his sister Hattie died; in May, his brother Frank—who had worked beside him for years at the Kaufman sawmill—was also lost.29 Coming on the heels of those deaths, the home on Mill Street that had often been filled with music and dancing, and that had watched children grow into adulthood, was destroyed by fire when an oil stove exploded in September.30 Furniture and possessions accumulated over decades vanished overnight. Once again, George and Edith turned inward to family for shelter, staying with their daughter Geraldine and her family. The response was not upheaval but recognition—an understanding, honed over a lifetime, that loss did not require reinvention. By late life, endurance had become habitual. For George and Edith, loss was no longer an ending, but another condition to be managed.

George and his sister Dora at the time of Edith’s funeral

Source: author’s personal collection

Five years later, George’s perseverance was tested in a way unlike any other loss. Edith’s death in November 1967 ended a forty-eight-year partnership forged through shared labor, hardship, and mutual reliance.31 For nearly half a century, Edith had been the steady center of George’s life—the manager of the household economy, the emotional anchor of a large and interdependent family, and the constant presence around which work, children, and community revolved. Family members later recalled that George was heartbroken, believing that with Edith’s death he had lost his greatest purpose. A photograph taken on the day of her funeral captures the weight of that loss. George stands beside his sister Dora—his final surviving sibling—two siblings who had lost their mother in childhood and were now reunited in mourning nearly seventy years later. The grief that had shaped George’s earliest years returned at the end of his life, not as a distant memory but as lived experience. Edith’s death did not merely mark the close of a marriage; it closed the emotional structure that had sustained George across decades of labor, loss, and endurance.

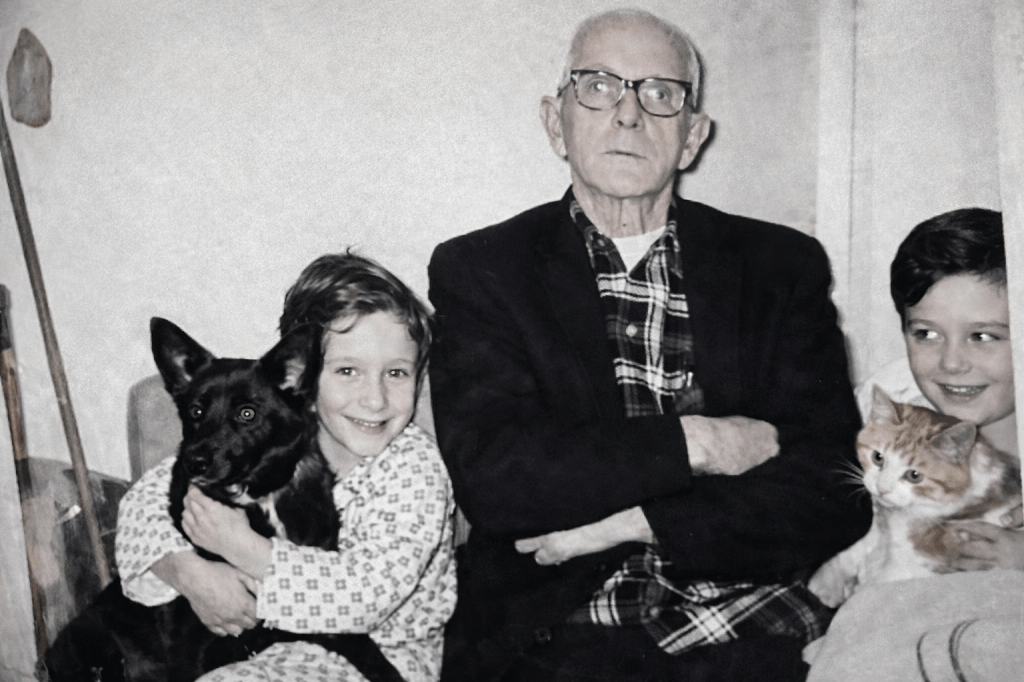

George in his later years with three of his grandkids

Source: author’s personal collection

In the years following Edith’s death, George lived quietly in Perry’s Mills, his world narrowed by age, loss, and habit, even as it expanded through the presence of the generations he had lived long enough to see. By then, he was surrounded by the nearby lives of thirty-five grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren—a measure not of abundance, but of continuity. Photographs show him holding grandchildren; family memories recall him kneeling beside them for bedtime prayers. In these final years, George relied on the same anchors that had sustained him throughout his life: family, faith, and familiarity.

On April 24, 1970, that long pattern of endurance ended suddenly when George was struck and killed by a car while crossing the road near his home. He had never learned to drive, remaining dependent on others even as automobiles reshaped American life. His death was ruled accidental—a final reminder of the vulnerability that accompanied old age and the risks that had shadowed his life in different forms from youth onward. He was seventy-seven years old.32

George Phaneuf’s life unfolded within narrow boundaries: the mill, the road, the family, the seasons. He worked with his hands, remained in the place of his birth, and raised his children amid persistent economic constraint. Through early loss, industrial danger, depression, war, and repeated personal grief, he endured—not with spectacle, but with reliability.

The modest stone that marks his grave records only his name and dates, yet it stands for something larger. It marks a life shaped by family, steadied by faith, and sustained through the familiar rhythms of work and home. His legacy is not distinction, but continuity—a life held steady long enough for others to endure less, and to build more. His story is that of quiet perseverance: a working man navigating extraordinary change by remaining, always, at his post.

Endnotes

- Find a Grave, memorial page for George E. Phaneuf (1892–1970), Memorial ID 32873745, citing Saint Ann’s Cemetery, Mooers Forks, Clinton County, New York; maintained by Carol Guerin (contributor 46992307), accessed December 18, 2025.

- Ibid.

- Laura’s familial name was recorded at various times as Le Roi, Le Roy, King, and Roy. I’ve opted for the familial name as shown on her father’s grave in Old Saint Mary’s Cemetery, Champlain, NY.

- 1860 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Pauletto Fneffo household, dwelling 242 family 244, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Page: 597. Antoine’s father is recorded as a sawyer in the 1860 census, showing the family’s early entry into lumbering.

- 1870 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Bazziel King household, dwelling 586 family 600, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll M593_918, Page: 190A.

- 1880 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Antoine Faneuf household, dwelling 325 family 334, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll 819, Page: 180D.

- 1900 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Antoine Fenneff household, dwelling 286 family 286, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll 1018, Pages: 20A,20B.

- New York State Department of Health, “Laura Phaneuf death entry, 1898,” New York State Death Index, 1880–1956, Ancestry.com, citing Certificate Number 12989; accessed December 18, 2025.

- For more information on the profound impacts that high mortality rates had on the 19th-century American family, see Steven Mintz and Susan Kellogg, Domestic Revolutions (New York: Free Press, 1988). They shed light on the experience of child bereavement, including both the psychological impacts of death and the culture of mourning.

- 1900 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Antoine Fenneff household, dwelling 286 family 286, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll 1018, Pages: 20A,20B.

- 1910 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Antoine Pheneuf household, dwelling 51 family 52, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com:accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll T624_932, Page: 10A.

- For more information on the brutal conditions of the lumber industry, see Philip J. Terrie, Contested Terrain: A New History of Nature and People in the Adirondacks (2008).Terrie describes the Adirondack lumber industry as an “unforgiving environment” where the pressure for productivity in the mills of Northern New York often resulted in the horrific accidents.

- “Ski making business flourished in Champlain,” Press-Republican, February 23, 1980, page 6.

- “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918,” digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed December 18, 2025), entry for George Phaneuf, Clinton County, New York; citing World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, NARA microfilm publication M1509, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

- “Lumber Co. Landmark in Perry’s Mills,” Plattsburgh Press-Republican, January 27, 1958, page 16.

- George Phaneuf and Edith Mesick marriage entry, September 1, 1919, New York State Marriage Index, 1881–1967 [database on-line], Ancestry.com (accessed December 18, 2025); citing New York State Department of Health, Albany, New York.

- 1920 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Antoine Phaneuf household, dwelling 162 family 163, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com:accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll T625_1094, Page: 8A.

- 1930 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, George Pheneuf household, dwelling 92 family 93, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com:accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll 1416, Page: 5A.

- For more information on the impact of the Great Depression, see David E. Nye, Hardship and Hope: Rural America During the Depression (New York: Routledge, 1995).

- 1940 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, George Pheneuf household, family 20, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com:accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll T627_2516, Page: 10B.

- Ibid.

- Floyd G. Phaneuf entry, enlistment date February 8, 1944, service number 42121414, “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938–1946,” [database on-line], Ancestry.com (accessed December 18, 2025); citing National Archives and Records Administration.

- For more information on the war in the Pacific during WWII, see John Dower, War Without Mercy (New York: Pantheon, 1986).

- “31-Year-Old Man Seriously Injured in Mill Accident,” Plattsburgh Press-Republican, December 28, 1946, page 3, column 6.

- 1950 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, George Phenuf household, house 20 dwelling 169, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com:accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, NAID 43290879, Sheet: 22.

- “Floyd G. Phaneuf,” obituary, The Post-Star (Glens Falls, NY), October 16, 1995, B5. To cite the obituary for Kenneth B. Phaneuf from the Press-Republican in Chicago style, use the following formats. Based on the source, this was published on December 9, 2016. “Kenneth B. Phaneuf,” obituary, Press-Republican (Plattsburgh, NY), December 9, 2016, https://obituaries.pressrepublican.com/obituary/kenneth-phaneuf-854148202.

- “Obituary,” Plattsburgh Press-Republican, April 16, 1947, page 5, column 8.

- Find a Grave, memorial page for Lorena Guerin (1876–1956), Memorial ID 32873721, citing Saint Joseph’s Cemetery, Coopersville, Clinton County, New York; maintained by G.L. LaFontaine (contributor 47472479), accessed December 18, 2025. Lorena Phaneuf Guerin death report, February 24, 1956, in “Reports of Deaths of American Citizens Abroad, 1835–1974,” Record Group 59 (General Records of the Department of State), Entry 205, Box 971, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; accessed December 18, 2025, via Ancestry.com.

- Find a Grave, memorial page for Hattie Edith Pheneuf Meseck (1894–1962), Memorial ID 168875409, citing Saint Ann’s Cemetery, Mooers Forks, Clinton County, New York, accessed December 22, 2025. Find a Grave, memorial page for Frank Xavier Phaneuf (1884–1962), Memorial ID 284041423, citing New Saint Mary’s Cemetery, Champlain, Clinton County, New York, accessed December 22, 2025.

- “Fire Routs Family of 3,” Plattsburgh Press-Republican, September 4, 1962.

- “Mrs. Edith Phaneuf,” obituary, The North Countryman (Rouses Point, NY), November 16, 1967, page 25, columns. 4–5.

- “George Phaneuf,” obituary, The North Countryman (Rouses Point, NY), April 30, 1970, page 24, column 5.

Wonderful piece Darren! George and Edith’s lives represent so many folks whose stories are never recognized as important to our history! Something that intrigues me about Edith and so many women of her time is how she felt about having so many children. She didn’t in reality have much choice and the strain on her body and health was incredible. Years ago I interviewed quite a few women who only had 2-4 kids who admitted to wishing they had not had so many or even any children! All, however, said that once the kids arrived, they loved them. And this was in a time when motherhood was seen as almost sacred! Sorry for a long digression but your story was so well done it made me think!

LikeLike

Thanks so much, Dr. Waller. I wish I could turn back the clock a little and be able to talk with people like George and Edith.

LikeLike