James Tankard’s grave in County Home Cemetery, Beekmantown, NY

Source: Find A Grave

In the County Home Cemetery in Beekmantown, New York, a simple grave marks the life of James Tankard, recording only the barest facts: a name, a date of death, an age…a life reduced to its beginning and end.1 The cemetery serves as the burial ground for those who died in the Clinton County Poorhouse—a final resting place for people who ended their lives dependent on public charity, without family or resources to secure a private burial. That James’s story concludes in the County Home Cemetery, however, obscures the life he actually lived. A closer examination of his life reveals both the possibilities and the constraints faced by Black citizens in nineteenth-century upstate New York.2 Through James’s experiences, we can glimpse how small rural communities navigated race, obligation, and care for their most vulnerable members before the rise of modern social welfare systems.

To fully understand James’s life, one must first understand why a Black community existed in northern New York at all. The community into which James Tankard was born developed out of the earliest patterns of Black settlement in Clinton County, patterns shaped by slavery, gradual emancipation, and the labor needs of northern New York in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. One of the earliest documented concentrations of free Black residents can be traced to the estate of Thomas Tredwell, a Princeton-educated lawyer and former member of the Continental Congress who relocated from Smithtown, Long Island, to the area in 1793.3 Tredwell emancipated many of the enslaved people that joined him on the relocation to Clinton County, and they settled upon a tract of elevated land that became known locally as “Richland” initially and later “Bear Town” or “Little Africa”4. The first few decades of the 1800s saw a growing population of free Black adults and children as Richland became an anchor point for attracting Black residents to northern New York. These settlements remained small, vulnerable, and closely tied to local labor markets, yet they provided the social world into which families like the Tankards were born and from which they would later struggle to remain.

James Tankard was born in March 1833 in Plattsburgh, New York, into a family already established within the region’s small but significant free Black community.5 His father, George Tankard, had moved to the area from Dorset, Vermont.6 George married Isabel Soper, and he first appears in New York records in 1819, when he presented his certificate of freedom to Plattsburgh town officials—one of several bureaucratic requirements imposed on Black men seeking to exercise the franchise. Although New York had begun gradual emancipation in 1799 and achieved full emancipation on July 4, 1827, freedom did not translate into equality. Black men faced property requirements for voting that few could meet, and daily life was shaped by newspaper denunciations, condemnation of interracial marriage, and segregation even in churches. His brother Martin obtained the same certification in 1821.7 This seemingly routine administrative act, preserved in town meeting minutes, speaks volumes about the Tankard family’s determination to assert their citizenship and belonging in a community that imposed both formal and informal barriers to Black participation.

The 1820 census recorded George Tankard, then a young man, living in Plattsburgh with two other free people of color—almost certainly his wife Isabel and their first child. Because the Plattsburgh census was arranged alphabetically rather than geographically, reconstructing neighborhood proximity is difficult. Nevertheless, the household was listed as engaged in agriculture, suggesting that George worked the land in some capacity, likely as a hired laborer or tenant farmer.8 Among the six other Black nuclear families recorded in Plattsburgh in 1820 was one headed by Sampson Soper.9 Although documentary evidence remains limited, Sampson was likely related to James’s mother Isabel—quite possibly her father—pointing to the existence of extended kin networks among the town’s small free Black population.

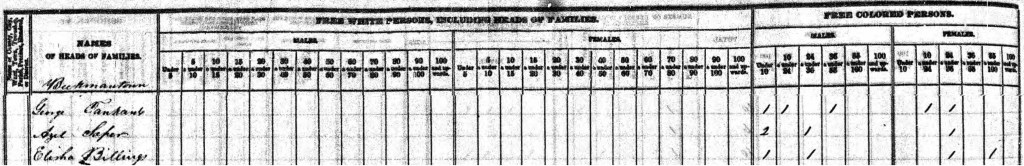

By 1830, George Tankard’s household had grown to six people. The census lists George and Isabel, three young children—two boys and a girl under the age of ten—and an older woman who was likely an extended family member.10 Although the number of Black nuclear families in the town had declined from seven to four over the previous decade, all four remaining households had been residents for more than ten years, suggesting continuity rather than instability. Of the 800 families listed in the 1830 census for the town, the household headed by Sampson Soper appears just eight houses away from George Tankard’s growing family—a small but telling reminder of the proximity and persistence of these early Black kin and community networks.11

The Tankard family in 1840

Source: 1840 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Beekmantown Township.

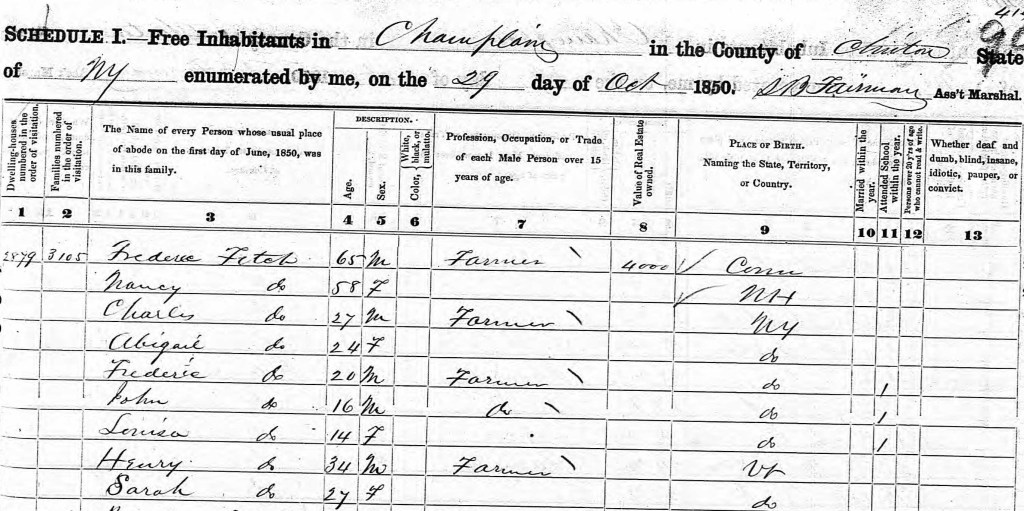

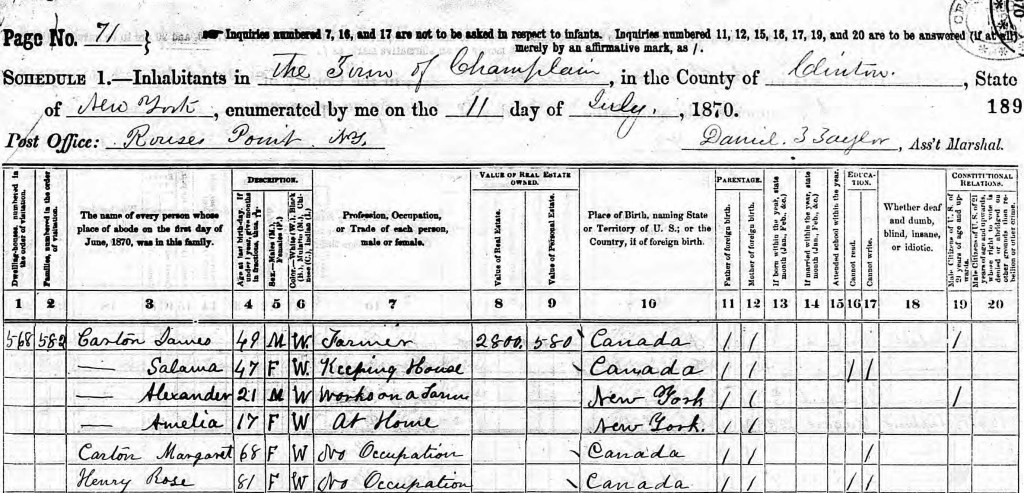

James’s early childhood unfolded amid a quiet but consequential shift in place. Sometime in the 1830s, the Tankard family left Plattsburgh and resettled just a few miles north in Beekmantown, moving into the orbit of the Black settlement that had taken shape around Richland. When the census taker arrived in 1840, James was about seven years old, and George Tankard headed a household of five, working in agriculture.12

The move placed the Tankards within a small, concentrated Black neighborhood. Of the fourteen Black residents recorded in Beekmantown that year, all but one lived in close proximity to the Tankard household. James grew up alongside the four-member families headed by Azel Soper and Elisha Billings.13 Azel—likely Isabel’s brother—had made the same move from Plattsburgh at roughly the same time, suggesting a kin-based migration into a space already shaped by earlier Black settlement.

In a town that was otherwise almost entirely white, James’s childhood unfolded in daily contact with people who shared his family’s history and status. That proximity was not accidental. The Tankards’ move placed James within one of several established geographies of Black settlement in northern Clinton County, mirrored in nearby towns such as Redford, Altona, and Chazy. The settlement in Redford, for example, was anchored by the work of James’s uncle Martin Tankard, a noted melt master at the Redford Glass Company whose labor sustained both family and community.14

These neighborhoods offered Black families spaces of relative autonomy from white scrutiny, often on the outskirts of towns where physical isolation—and the dangers of the surrounding woods—was exchanged for a measure of safety and self-determination. The clustered households surrounding James offered more than convenience; they provided continuity, mutual recognition, and a sense of belonging that was rare for Black children growing up in rural northern communities, buffering—though never eliminating—the insecurity of life in a society that tolerated Black presence without fully accepting it.

Even as sentiment in Beekmantown began to shift in modest ways—reflected in an 1846 town vote supporting equal voting rights for Black citizens—the daily reality remained one of separation and constrained opportunity.15 Expressions of principle did not dismantle the social boundaries that shaped where Black families lived, worked, or belonged. For the Tankards, the 1840s appear to have been a period of quiet transition, as the neighborhood networks that had defined James’s childhood began to thin, leaving family rather than community as the most consistent source of stability.

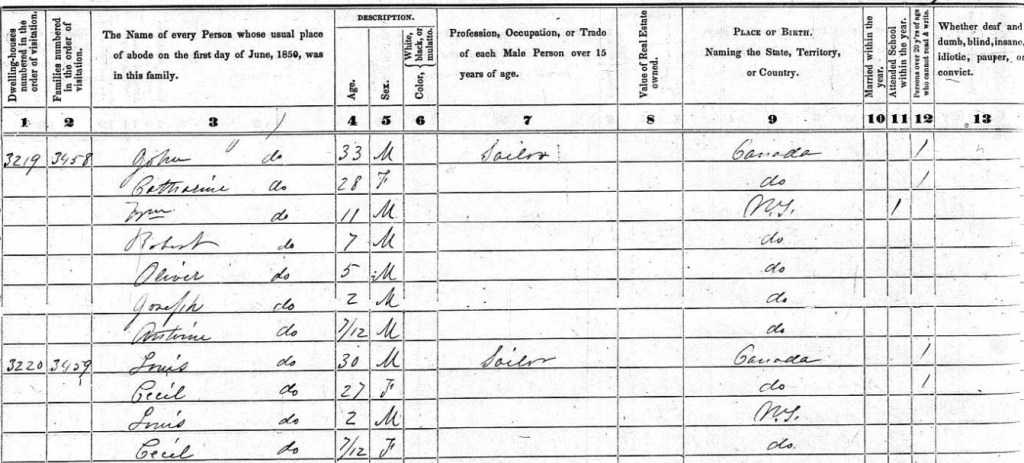

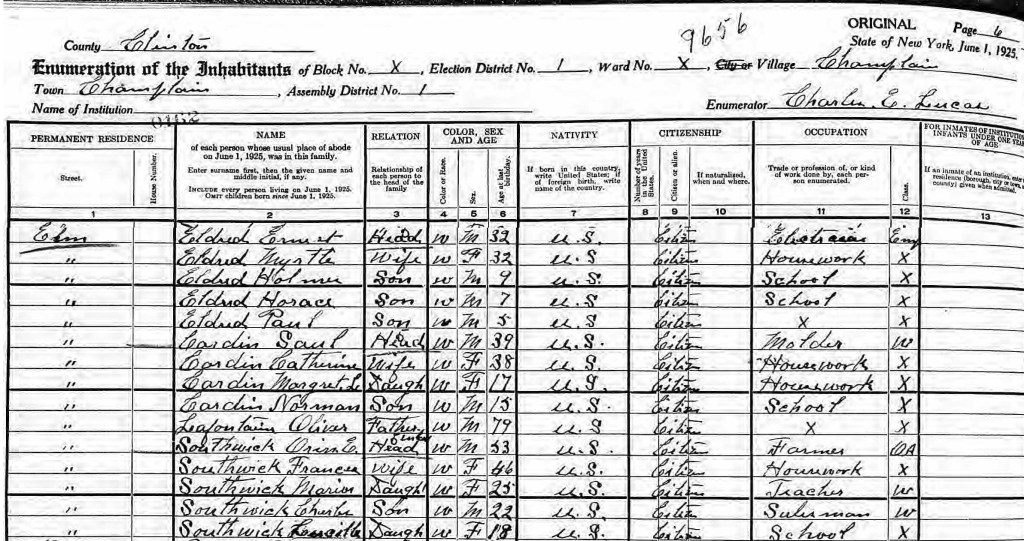

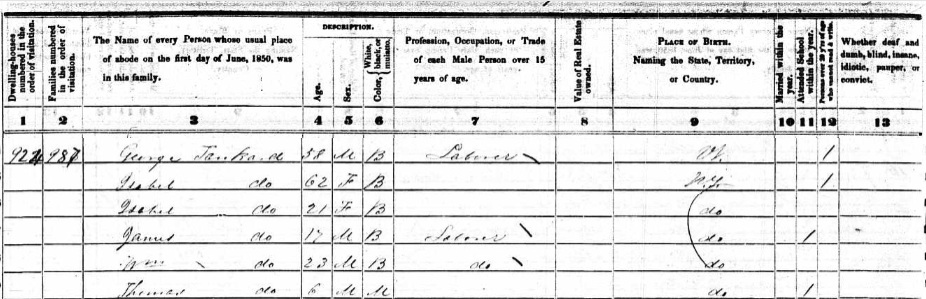

The Tankard family in 1850

Source: 1850 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Beekmantown Township.

The 1850 census provides our first direct glimpse of James Tankard as an individual. At seventeen, he lived with his parents, George (now fifty-eight) and Isabel (sixty-two), along with several siblings, including William (twenty-three), Isabel Jr. (twenty-one), and the youngest, Thomas (six). James worked as simply a laborer. Both he and Thomas had attended school in the last year.16 Repeated newspaper notices over more than two decades indicate that Isabelle Tankard regularly received letters at the Plattsburgh post office—evidence not only of functional literacy, but of sustained correspondence that connected the family to people beyond their immediate community.17 Despite that evidence, James is noted as unable to read and write for much of his life. Unlike earlier censuses, the 1850 enumeration places the Tankard household without other Black families immediately nearby, a shift that reflects changing patterns of residence within the town.

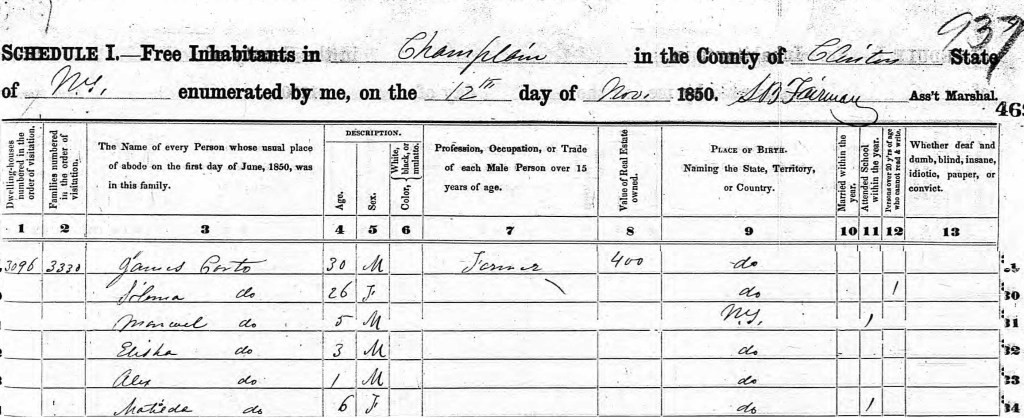

Because the 1850 census recorded every resident by name, it provides the first opportunity to examine the full spatial world occupied by Black residents of Beekmantown. That world was a constrained one. Six people of color were incarcerated in the state prison that would eventually become part of the distinct town of Dannemora. Another Black resident lived in the town poorhouse. The census thus locates a significant portion of Beekmantown’s Black population within systems of confinement or dependency rather than independent household formation.

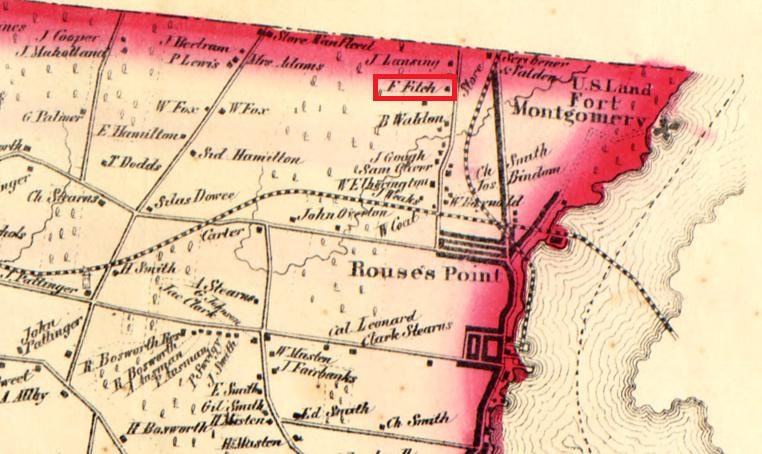

Outside of these institutions, a small number of Black families resided independently within the town. It is among these households that the Tankards’ position can best be understood. Among the free Black families living outside institutional care were a few that had achieved modest stability, often through skilled labor and limited property ownership. Azel Soper, the relative who had lived alongside the Tankards in 1840, remained in Beekmantown in 1850. He supported a family of five as a joiner and held real estate valued at $200. His teenage son worked as a laborer, and both he and his younger brother attended school—mirroring the educational efforts evident within the Tankard household and underscoring the role of stability in sustaining schooling.18 George Nutt headed another Black nuclear family and, like Soper, owned real estate, though valued more highly at $400.19 Nutt was the only Black resident of Beekmantown listed as a farmer and the only one whose household appeared on the 1859 town map, a rare visibility that underscores both his relative standing and the exceptionality of such recognition for Black residents.20 Together, Soper and Nutt represent the upper bound of economic security available to Black families in Beekmantown—achieved through skilled labor, property ownership, and careful navigation of a racially restrictive economy.

Other Black households occupied far more precarious positions, revealing how thin the line was between independence and dependency. Eighty-year-old Jacob Oakley and his son Francis occupied one house. Jacob himself was still listed as a laborer, underscoring how necessity—not longevity or security—dictated continued work even into old age. Nearby lived eighty-year-old Jenny York, whose household included Selinda Billings and her eleven-year-old son Charles, who attended school during the previous year. Both the Oakley (in 1820) and York (in 1830) surnames were previously found in Beekmantown census. York and Billings were listed as paupers in 1850—an important distinction.21 Of the three town residents receiving poor relief outside the poorhouse in 1850, two were Black women. The fact that two of the three town residents receiving poor relief outside the poorhouse were Black women underscores just how narrow the margin was between independence and dependency for African Americans in mid-century Beekmantown.

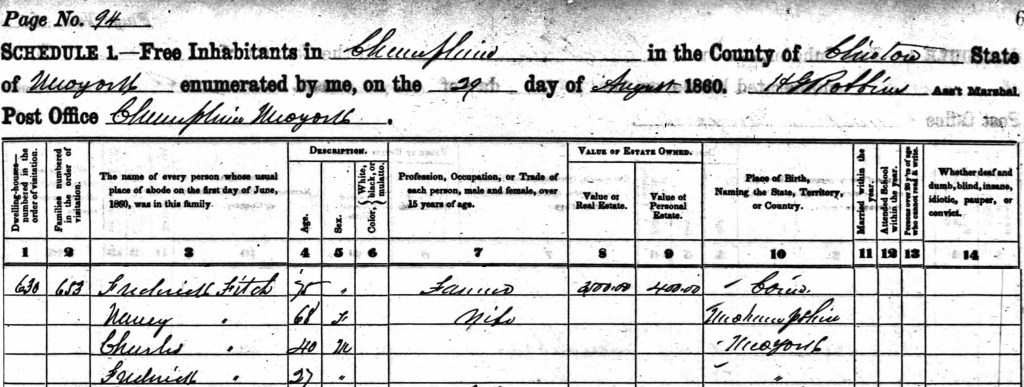

James’s return to Plattsburgh by 1860 marked another reconfiguration of his household and family ties. Now twenty-seven and still working as a laborer, he resided with only his mother, Isabel, who at seventy-eight had outlived James’s father. Two siblings were no longer present—Isabel likely having established a household of her own, while the fate of the youngest, Thomas, remains unclear.22 James and his mother shared their dwelling with twenty-two-year-old Theodore Winchell, a Black man also employed as a hired laborer. This arrangement reflected the fluidity and enduring connections among Black families in the region: in 1850, Winchell had lived in a household with James’s sister, Jane. A decade later, he was married and living with his twenty-year-old wife, Martha, who was listed as white.23

Yet family proximity had not vanished entirely. The household listed immediately next to James’s belonged to his brother William, placing the two men side-by-side once more. William headed a growing family, living with his wife, Eliza, twenty-four, and their four young children—James, George, Mary, and Isabel. Like his brother, William supported his household through day labor. Echoing a pattern seen in several marriages forming around James, Eliza was white.24

Despite James’s return—and that of some family members—to Plattsburgh, connections to Beekmantown remained strong. His mother’s relative Azel Soper, once a skilled joiner and property holder, continued to reside there, though by 1860 he was listed simply as a laborer with no real estate, working alongside his eighty-one-year-old father, John.25 Among the Black families newly recorded in Beekmantown was the household of James Kelly and his wife, Jane. Supporting four young children, all under the age of seven, Kelly, like many others, relied on day labor.26 The Kelly household carried particular significance for James: Jane was his eldest sister, extending the Tankards’ kinship network and reinforcing their enduring presence in the town.

Taken together, these households reveal a pattern of geographic mobility and endurance. Black families in Beekmantown during the 1850s largely managed to remain—intact and often still neighboring one another—yet were increasingly vulnerable to forces that would soon unravel both household and community life.

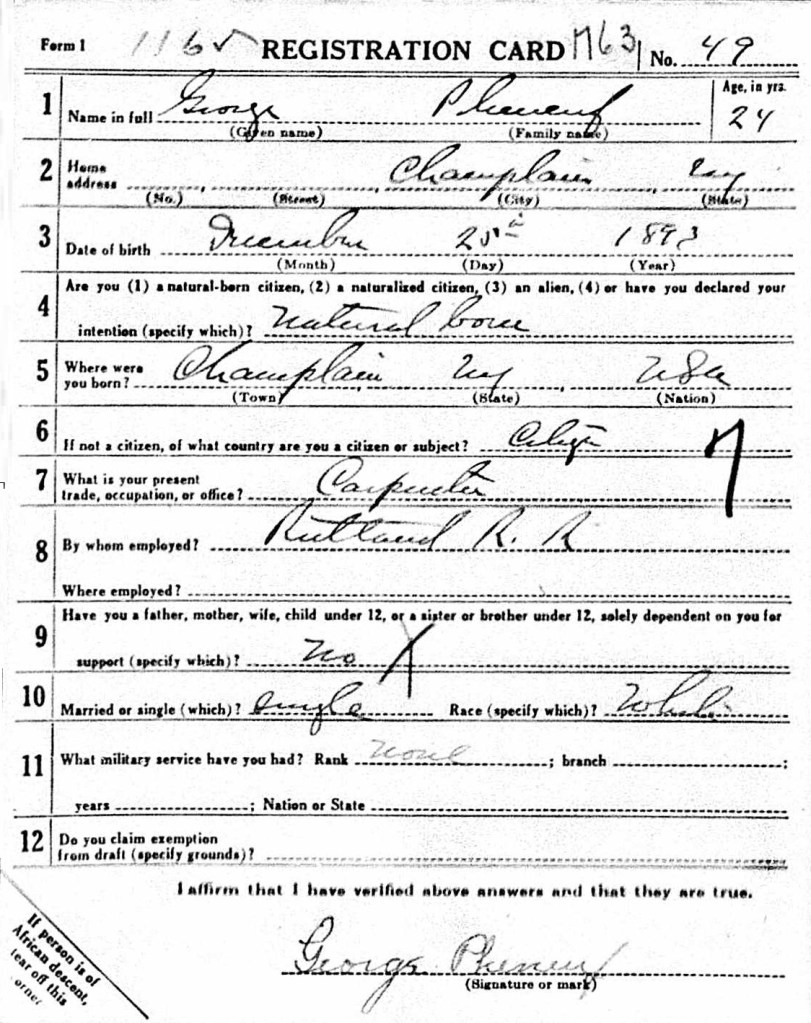

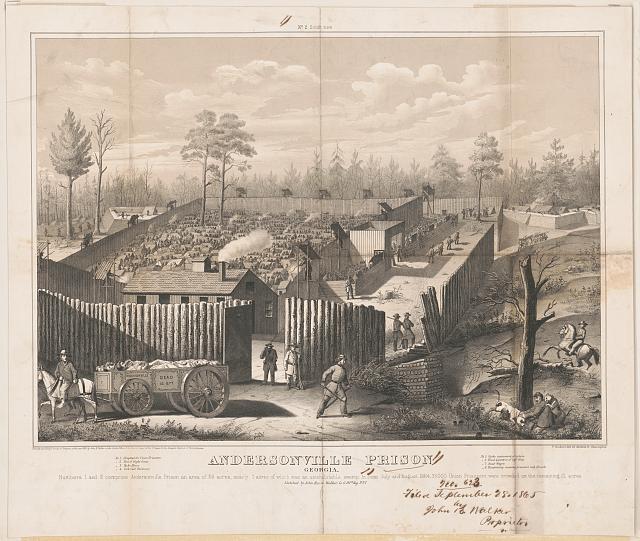

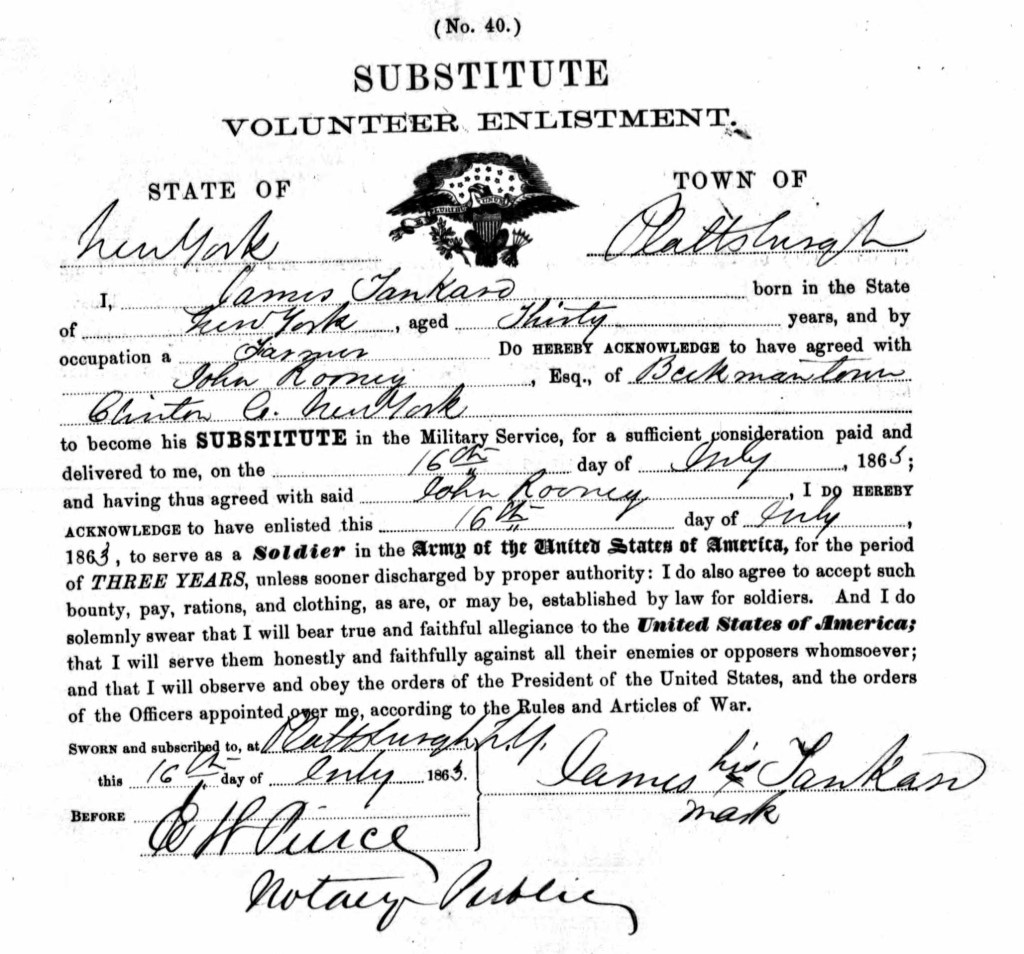

James Tankard’s substitute enlistment

Source: Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served With the United States Colored Troops

When President Lincoln authorized the enlistment of Black soldiers in 1863, James was in his early thirties, and working as a laborer. This would usher in the most consequential chapter of his life. That decision by Lincoln marked a turning point in the life of James. On July 14, 1863, he enlisted in Company H of the 8th United States Colored Infantry. His enlistment record captures him with precision: five feet eleven and a half inches tall, with black complexion, eyes, and hair, born in New York, and listing his occupation as “farmer.”27 Notably, James enlisted as a substitute, a legal arrangement under the federal draft system by which a drafted man paid another to serve in his place. In the case of James, he volunteered to fight on behalf of John Rooney.28 John was the son of William Rooney, a farmer with real estate valued at $6,000 in 1860 who had been listed a few houses away from Azel Soper on the 1850 census. Within days of being listed among men drafted in Beekmantown in July 1863, James had agreed to serve on Rooney’s behalf.29 For men like James, substitution offered wages and a bounty far beyond what agricultural labor could provide, even as it placed them in heightened danger. For Black men in particular, military service also offered the promise of recognition and citizenship in a nation that had long denied both. It was an opportunity forged from inequality and risk—a bargain many accepted because few alternatives existed.

While James enlisted on July 14, 1863, it would be months before he joined his regiment. The 8th United States Colored Troops, organized at Camp William Penn in Pennsylvania during the fall of 1863, was among the earliest regiments of Black soldiers formed after the Emancipation Proclamation.30 Composed largely of men who had labored as farmhands, laborers, and tradesmen, the regiment trained under white officers but fought under conditions shaped by race. Black soldiers faced the constant threat of unequal treatment if captured, lower pay for much of the war, and the expectation—often realized—that they would be assigned the most dangerous tasks. For James, enlistment meant entering not only the army but a proving ground where service itself was an assertion of manhood and citizenship.

James, whose life had been grounded in upstate New York, joined the 8th USCT when it deployed to Hilton Head, South Carolina, in January 1864. Within a month, he and the regiment faced their first combat at the Battle of Olustee on February 20, the bloodiest engagement of the war in Florida.31 Late in the battle, as Union forces began to retreat, the 8th was ordered forward to hold the line under intense Confederate fire. A lieutenant in Company K later described the men forming under fire with knapsacks still on and weapons unloaded, having run nearly half a mile before establishing a line scarcely two hundred yards from a concealed enemy. At first, the soldiers dropped to the ground as casualties mounted, but they soon regained their composure and returned fire. Their greatest disadvantage, he noted, was not fear but inexperience: “very little practice in firing, and, though they could stand and be killed, they could not kill a concealed enemy.”32

The cost for the regiment was devastating. Colonel Charles Fribley, the unit’s white commander, was killed, and of roughly 575 men present, 310 were killed, wounded, or missing—the highest casualty toll of any Union regiment at Olustee.33 Witnesses from both sides reported that some wounded Black soldiers who could not retreat were murdered rather than taken prisoner, reflecting the racialized violence faced by United States Colored Troops.34 For James, Olustee was an initiation by fire, a first confrontation with the mortal dangers of combat and an early lesson in the endurance, discipline, and courage demanded of Black soldiers.

James’s war became deeply personal on August 18, 1864. By then, the regiment had been transferred north to join Grant’s campaign against Petersburg, Virginia. Positioned at the extreme front behind hastily constructed breastworks at Deep Bottom along the James River, the 8th USCT came under a determined Confederate assault. When Union pickets were driven back and a supporting regiment withdrew from the right flank, James and his comrades were left dangerously exposed. Enemy forces, as reported by the major of James’s regiment four days after the battle, “pressed forward to the works on my right and to the edge of the woods in my front, but were soon compelled by the severity of my fire to retire.”35 Amid the confusion of that exchange, James was wounded severely in the shoulder.36

The injury ended his active service. Evacuated to Fort Monroe Hospital, James remained under medical care for the rest of the war. When he was finally mustered out on June 23, 1865—ten months after his wound—he was discharged for disability rather than completing his three-year enlistment.37 The war had offered James wages, purpose, and the promise of belonging; it returned him home permanently injured, but with an identity as a soldier that would endure long after his body could no longer sustain the labor on which independence depended.

When James returned to civilian life after the war, his world narrowed quickly. He applied for and was granted a pension based on the wound he had received at Deep Bottom, an early indication that the physical labor that had sustained him before the war would now be difficult to maintain.38 By 1870, his mother had died, severing the last tie to the household that had anchored him since childhood. James had settled once more in Beekmantown and married Margaret, a white woman sixteen years his junior. Their household included Margaret’s ten-year-old brother, William, and a five-year-old child, Emily Finegan, whose precise relationship to the family remains unclear. At thirty-seven, James continued to work as a farm laborer, despite the limitations imposed by his injury.39

Such stability as James achieved came largely through proximity. His brother William lived next door with his wife Eliza and their seven children, recreating—if only partially—the kin-based support that had defined James’s earlier life. Even here, continuity proved fragile. William’s son George boarded with a nearby family as a farm laborer, while his eldest son, James, disappeared from the historical record entirely—a reminder of how easily lives could slip beyond documentation in the nineteenth century.40 James’s sister Jane also remained in Beekmantown, living with her husband and six children. Like James and William, her husband James Kelly supported his household through farm labor.41

The wider Black community that had once buffered James’s childhood was thinning as well. Two of the families that had long shaped Black life in Beekmantown were gone by 1870. After Azel Soper’s death in 1864, property records show his family selling their land and leaving town.42 George Nutt and his family departed in 1865 for Pleasant Prairie Township, Minnesota, where Nutt and all of his children thereafter consistently identified as white in census records.43 Their departures marked more than geographic mobility; they signaled the unraveling of a community that had once included landowners, skilled tradesmen, and multigenerational households.

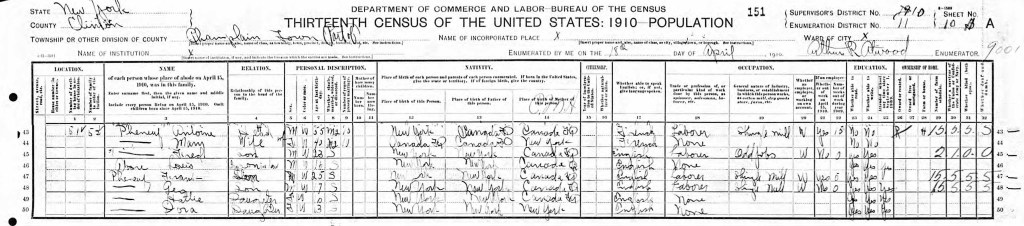

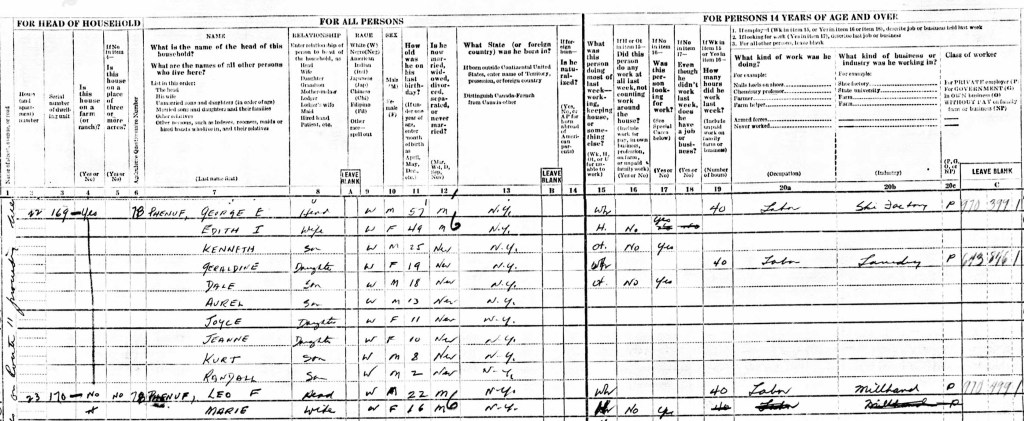

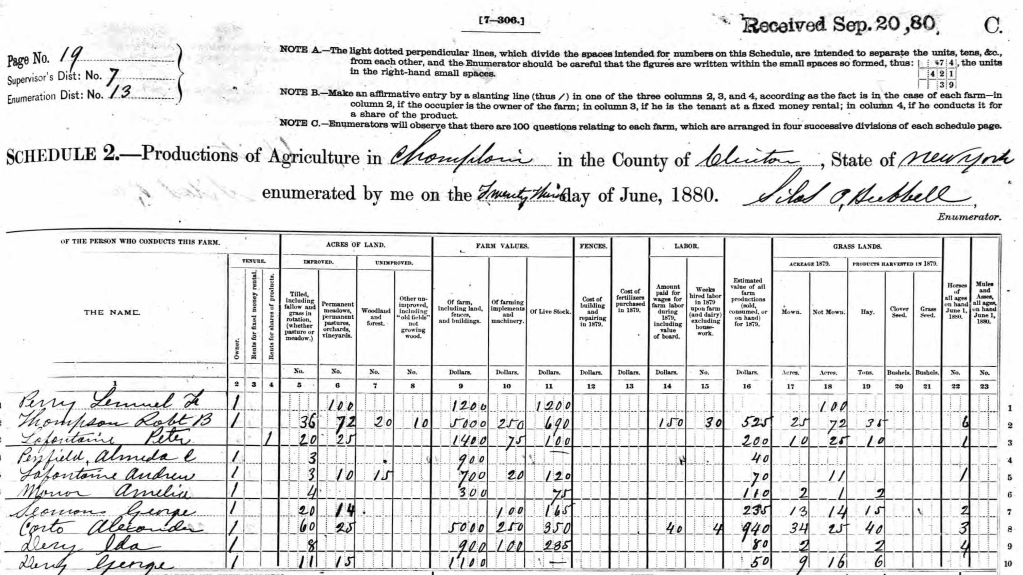

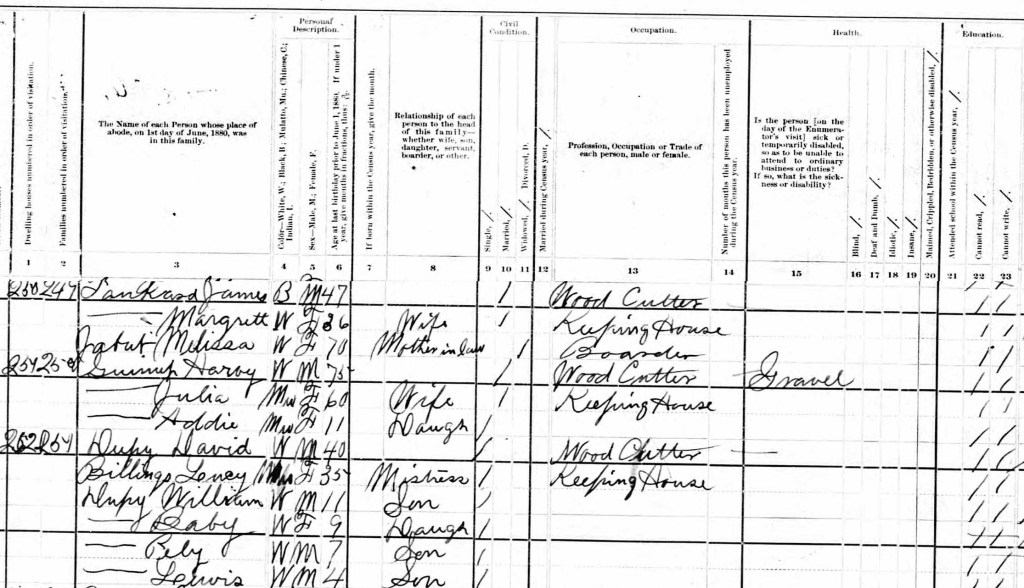

James and his family alongside their neighbors in the 1880 census

Source: 1880 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Beekmantown Township.

By 1880, James’s household had shifted yet again, reflecting both resilience and narrowing options. Now forty-seven, James was still listed as head of household and married to Margaret, then thirty-six. No children resided with them; instead, they followed a familiar pattern among Black families in Beekmantown, caring for Margaret’s seventy-year-old mother, Melissa Jabut. James had moved away from farm labor and was working instead as a woodcutter, felling timber in the forests that still covered much of Clinton County.44 It was punishing work—dangerous, physically exhausting, and poorly paid—but it was labor he could manage despite the lingering effects of his war wound. The hazards of the job were underscored by a brief notice in the local paper reporting that David Dupree, James’s neighbor and a fellow woodcutter, had “while chopping in the woods a week ago, gave his foot quite a severe gash with the axe.”45

The households surrounding James suggest that his own interracial marriage existed within a small but visible pattern of racial boundary-crossing that remained uneasy and closely scrutinized. His neighbor David Duprey, a white man living with his four children, also cohabited with a Black woman, Lucy Billings. In a town of more than 2,600 residents, Lucy was the only person described in the census as a “mistress,” a label that appears less descriptive than corrective—an attempt by the census taker to impose distance on a relationship that defied accepted norms.46 Like James and Margaret, Duprey and Billings occupied a social space that was neither hidden nor fully acknowledged, their domestic lives recorded in ways that reveal as much about white discomfort as about Black presence.

The Black community that had once surrounded James was steadily thinning. His brother William remained in Beekmantown with his wife and six children but no longer lived nearby.47 Foreshadowing a broader pattern, his sister Jane had moved across Lake Champlain to Burlington, Vermont, where her husband and five children were working; even eleven-year-old Orville was employed in odd jobs at a milling store rather than attending school.48 The remaining Black households in Beekmantown were small—no more than four people in any dwelling—and all were newcomers, reflecting a fragile persistence rather than rooted continuity. Sometime in the 1880s, James himself left Beekmantown and moved south to the hamlet of Redford in the town of Saranac, following cousins who had settled in the area where his Uncle Martin had once worked at the Crown Glass Works.

Despite decades of exhausting manual labor, James did not relinquish his identity as a soldier. On June 23, 1888—exactly twenty-three years after his discharge from the Union Army—he joined the Grand Army of the Republic. He listed his occupation as “farmer,” and appears on the muster roll alongside George Tankard of Redford, his cousin and the son of his Uncle Martin—a quiet reminder that military service remained a shared family legacy within the Tankard family. James’s GAR record carefully preserved the details of his wartime service in Company H of the 8th United States Colored Infantry, including his discharge for disability, affirming a chapter of his life that civilian records often reduced to labor alone.49

For Black veterans like James, the GAR offered something rare in the postwar North: recognition without formal racial exclusion, fellowship, and a collective voice in the struggle for pensions and respect. James remained active in the organization for six years, from 1888 until his suspension in 1894 and removal from the rolls in 1895.50 While the records do not specify the cause, such removals were often linked to an inability to pay dues or declining health that made attendance difficult. By the mid-1890s, James was in his early sixties, his wartime injury compounded by decades of physical labor. His disappearance from the GAR rolls does not suggest indifference, but rather the narrowing economic margins of an aging Black veteran whose service was honored in principle, if not fully supported in practice. Even so, James continued to participate in veteran life: when the 12th annual reunion of the Clinton County Union Veteran’s Association was held at a GAR post just outside Plattsburgh in September 1900, he was among the attendees noted in the newspaper.51

The 1890 veterans census still captured James in a familiar posture: fifty-seven years old and living in Saranac, the community where descendants of his Uncle Martin continued to reside. Despite the passage of time, James identified without qualification as a veteran of a United States Colored Troops regiment. His record noted a twenty-six-year struggle with chronic diarrhea, alongside a shoulder wound sustained during his service—a reminder that the war remained present in his body long after it had ended.52

A decade later, that stability had quietly eroded. By 1900, James was sixty-seven, widowed after Margaret’s death sometime in the previous decade, and living not with family but as a boarder in the house of Henry Lord in Ellenburg—a marginal and dependent position.53 His departure from Beekmantown to Redford in the 1880s and again to Ellenburg by 1900 echoed a wider pattern of dispersal among Black residents in the region. The census listed James as a “day laborer,” but also recorded that he had been unemployed for eight months of the previous year. At his age, burdened by old war wounds and decades of physical labor, the hardest work was no longer available to him, while the lighter work went to younger men.

For the second time in his life, the census noted that James could read and write. Whether this reflected an enumerator’s assumption, James’s own assertion, or a fragile skill acquired late in life remains unclear, but the timing is telling: literacy appears in the record only when it could no longer secure independence. What remains visible instead is a man who had outlived his strength, his wife, and the community that once anchored him.

A closer look at the Black community in Beekmantown in 1900 helps explain why James ultimately turned elsewhere. The community that had sustained Black families throughout much of the nineteenth century was nearly gone. Only two households included people of color: the family of one of James’s nephews and a Tankard cousin listed as an invalid boarder.54 The dense network of kin, neighbors, and shared labor that had once made survival possible had effectively collapsed. When the census taker returned a decade later, even that remnant had disappeared; the lone Black resident of Beekmantown was recorded not in a household, but in the County Poor House.55 In this context, James’s move to Ellenburg appears less as a choice than a necessity—a search for shelter and support in a town where any such network still existed.

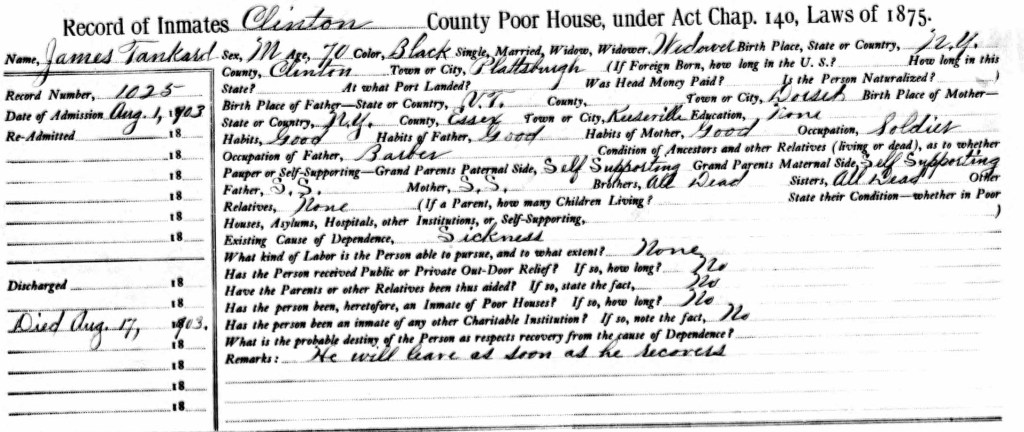

James Tankard’s admission paperwork to the County Poorhouse

Source: New York State Archives; Albany, New York; Census of Inmates in Almshouses and Poorhouses, 1875-1921

The final chapter of James Tankard’s life unfolded quietly in the summer of 1903. On August 1, he was admitted to the Clinton County Poorhouse in Beekmantown, returning in sickness to the place where he had been born seventy years earlier. The admission record reduces a long life to a handful of stark facts: Black, widowed, born in Plattsburgh, with no formal education and no living relatives.56 His brother William—so long a constant presence—had died two years earlier, removing the last pillar of family support.57 The cause of James’s dependence was listed simply as “sickness.” When asked what kind of labor he could perform, the answer was “none.”58

Under occupation, James did not record the work that had consumed his body—woodcutting, day labor, decades of physical toil. Instead, he wrote “soldier.” It was the identity that had once given his life purpose and standing, and the one he chose to carry with him at the end. In the remarks column, the superintendent noted with routine optimism, “He will leave as soon as he recovers.” James Tankard never recovered. He died seventeen days later, on August 17, 1903.59

James Tankard’s grave in the County Home Cemetery in Beekmantown—the potter’s field for those who died dependent on public charity—stands as a final measure of both endurance and erasure. For decades, James lived a life marked by labor and care, sustained by a resilient network of Black households that once anchored Beekmantown through work and kinship. But by 1903, the informal networks that had absorbed age, injury, and loss were gone. When James grew too old to work and was left alone by his wife’s death, there was nothing left to support him but the poorhouse—a fate that was not a failure of character, but the result of a world in which labor sustained life only as long as the body held. Yet, even as the community that once sustained him vanished around him, James remained the architect of his own story. By declaring himself a ‘soldier,’ he ensured that his last official record would reflect not how he had toiled, but the identity he had claimed through his service.

Endnotes

- Find a Grave, “James Tankard (1833–1903),” Memorial 94997655, citing County Home Cemetery, Beekmantown, Clinton County, New York, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/94997655/james-tankard.

- In this study, the term “Black” is used to describe individuals whom nineteenth-century census enumerators variously classified as “Black” or “mulatto.” These distinctions reflected the assumptions and practices of census takers rather than meaningful differences in legal status or lived experience. For the purposes of this analysis, a unified term is used to emphasize the shared social, legal, and economic position of nonwhite residents in Beekmantown, while avoiding the reproduction of racial categories that were inconsistently applied and historically contingent.

- William A. Robbins and Elizabeth Ellen Schnebly Treadwell, Descendants of Edward Tre(a)dwell through His Son John (New York: T.A. Wright Press, 1911), 78. Tredwell’s relationship to slavery reflected the contradictions that were common among elite New Yorkers during the period. During the New York ratifying convention in 1788, he publicly condemned slavery, yet he brought forty enslaved people with him when he moved to northern New York and still held slaves as late as 1810.

- Ibid.

- 1900 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Ellenburg Township, Henry Lord household, dwelling 182 family 182, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll 1018, Pages: 10.

- “James Tankard,” Record no. 1025, Census of Inmates in Almshouses and Poorhouses, 1875–1921, Reel A1978:20, Series A1978, New York State Archives, Albany, New York.

- Philip L. White, Beekmantown, New York: Forest Frontier to Farm Community (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1979), 177.

- 1820 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Plattsburgh Township, George Tankard household, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M33, Roll 66, page 472.

- 1820 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Plattsburgh Township, Sampson Soper household, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M33, Roll 66, page 468.

- 1830 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Plattsburgh Township, George Tankard household, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M19, Roll 85, page 263.

- 1830 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Plattsburgh Township, Sampson Soper household, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M19, Roll 85, page 263.

- 1840 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Beekmantown Township, George Tankard household, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication Roll 276, page 215.

- 1840 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Beekmantown Township, Azel Soper and Elisha Billings households, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication Roll 276, page 215.

- Warner McLaughlin, “A History of the Redford Crown Glass Works at Redford, Clinton County, N. Y.,” New York History 26, no. 3 (1945): 370.

- White, Beekmantown, 106.

- 1850 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Beekmantown Township, George Tankard household, dwelling 924 family 987, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M432, Roll 489, page 314b.

- “List of Letters,” Plattsburgh Republican (NY), notices for Mrs. Isabelle Tankford: July 14, 1838, 1; July 21, 1838, 3; October 6, 1838, 3; January 5, 1839, 3; January 19, 1839, 3; July 13, 1839, 1; October 1, 1842, 3; October 8, 1842, 1; January 2, 1847, 3; January 9, 1847, 1; October 6, 1849, 3; October 13, 1849, 3; January 19, 1850, 1; July 6, 1850, 3; July 13, 1850, 1; December 4, 1858, 3.

- 1850 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Beekmantown Township, Azel Soper household, dwelling 139 family 141, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M432, Roll 489, page 10b.

- 1850 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Beekmantown Township, George Nutt household, dwelling 955 family 1019, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M432, Roll 489, page 316b.

- A. Ligowsky, Map of Clinton Co., New York (Philadelphia: O. J. Lamb, 1856), map, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2009583837/.

- 1850 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Beekmantown Township, Jacob Oakley household, dwelling 956 family 1020, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M432, Roll 489, page 316b. 1850 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Beekmantown Township, Jenny York household, dwelling 957 family 1021, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M432, Roll 489, page 316b.

- 1860 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Plattsburgh Township, Isabel Tankford household, dwelling 736 family 880, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M653, Roll 736, page 876.

- 1860 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Plattsburgh Township, Theodore Winchell household, dwelling 736 family 879, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M653, Roll 736, page 876.

- 1860 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Plattsburgh Township, William Tankford household, dwelling 737 family 881, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M653, Roll 736, page 876.

- 1860 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Beekmantown Township, Azel Soper household, dwelling 1226 family 1126, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M653, Roll 735, page 342.

- 1860 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Beekmantown Township, James Kelly household, dwelling 963 family 886, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M653, Roll 735, page 309.

- James Tankard, entry in Company Descriptive Book, Company H, 8th U.S. Colored Troops, Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served with the United States Colored Troops: Infantry Organizations, 8th through 13th, National Archives, Washington, DC; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed January 11, 2026); citing NARA microfilm publication M1821.

- James Tankard, “Substitute Volunteer Enlistment,” 1863, Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served with the United States Colored Troops: Infantry Organizations, 8th through 13th, National Archives, Washington, DC; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed January 11, 2026); citing NARA microfilm publication M1821.

- “List of Men Drafted from the County of Clinton,” Plattsburgh Republican (Plattsburgh, NY), July 18, 1863, 3, col. 1.

- Frederick H. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion: Compiled and Arranged from Official Records of the Federal and Confederate Armies, Reports of the Adjutant Generals of the Several States, the Army Registers, and Other Reliable Documents and Sources (Des Moines, IA: Dyer Publishing Co., 1908), 1725.

- Ibid.Oliver Willcox Norton, Army Letters, 1861–1865: Being Extracts from Private Letters to Relatives and Friends from a Soldier in the Field during the Late Civil War (Chicago: O. L. Deming, 1903), 198.

- Oliver Willcox Norton, Army Letters, 1861–1865: Being Extracts from Private Letters to Relatives and Friends from a Soldier in the Field during the Late Civil War (Chicago: O. L. Deming, 1903), 198.Samuel P. Bates, History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5: Prepared in Compliance with Acts of the Legislature, vol. 5 (Harrisburg: B. Singerly, 1871), 966.

- Samuel P. Bates, History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5: Prepared in Compliance with Acts of the Legislature, vol. 5 (Harrisburg: B. Singerly, 1871), 966.Angela M. Zombek, “The Battle of Olustee,” American Battlefield Trust, last modified August 3, 2023, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/battle-olustee.

- Angela M. Zombek, “The Battle of Olustee,” American Battlefield Trust, last modified August 3, 2023, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/battle-olustee.

- George E. Wagner, “Report of Maj. George E. Wagner, Eighth U.S. Colored Troops, of Operations August 18,” August 22, 1864, in U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, vol. 42, pt. 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1893), 780.

- James Tankard, “Casualty Sheet of Wounded,” August 18, 1864, Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served with the United States Colored Troops: Infantry Organizations, 8th through 13th, National Archives, Washington, DC; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed January 11, 2026); citing NARA microfilm publication M1821.

- James Tankard, “Company Muster Roll,” August 1864-June 1865, Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served with the United States Colored Troops: Infantry Organizations, 8th through 13th, National Archives, Washington, DC; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed January 11, 2026); citing NARA microfilm publication M1821.

- James Tankard (Co. H, 8th U.S. Colored Infantry), Civil War Pension Index, application no. 75,072, certificate no. 608,634; General Index to Pension Files, 1861–1934, T288; National Archives, Washington, DC; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed January 11, 2026).

- 1870 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Beekmantown Township, James Tankard household, dwelling 164 family 163, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M593, Roll 918, page 84B.

- 1870 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Beekmantown Township, William Tankard household, dwelling 163 family 162, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M593, Roll 918, page 84B.

- 1870 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Beekmantown Township, James Kelly household, dwelling 361 family 355, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M593, Roll 918, page 97A.

- Find a Grave, “Azel T. Soper (1806–1864),” Memorial 106580999, citing Riverside Cemetery, Plattsburgh, Clinton County, New York, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/106580999/azel-t.-soper.

- 1880 US census, Martin County, Minnesota, population schedule, Pleasant Prairie Township, George Nutt household, dwelling 21, family 21, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll 626, page 163c.

- 1880 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Beekmantown Township, James Tankard household, dwelling 250 family 249, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication Roll 819, page 104D.

- “Rand Hill,” The Plattsburgh Sentinel (Plattsburgh, NY), January 4, 1889, 8.

- 1880 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Beekmantown Township, David Duprey household, dwelling 252 family 251, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication Roll 819, page 104D.

- 1880 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Beekmantown Township, William Tankard household, dwelling 114 family 106, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication Roll 819, page 96D.

- 1880 US census, Chittenden County, Vermont, population schedule, Burlington Township, James Kelly household, dwelling 11 family 12, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication Roll 1343, page 10C.

- James Tankard, entry in Descriptive Book, John S. Stone Post 352 (Saranac), Grand Army of the Republic Records, 1871–1928, Series B1706, New York State Archives, Albany, NY; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026).

- Ibid.

- “Clinton County Veterans,” The Plattsburgh Sentinel (NY), September 7, 1900, 1, col. 6.

- 1890 U.S. Census, Special Schedule – Surviving Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines and Widows, Saranac, Clinton County, New York, enumeration district (ED) 32, p. 1, line 21, James Tankard; National Archives Microfilm M123, roll 50; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026).

- 1900 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Ellenburg Township, Henry Lord household, dwelling 182 family 182, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication Roll 1018, page 10.

- 1900 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Beekmantown Township, William Tankard household, dwelling 138 family 140, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication Roll 1018, page 8.

- 1910 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Beekmantown Township, enumeration district (ED) 5, Charles Crassier, dwelling 192 family 193, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 2026); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication T624 Roll 932, page 9B.

- James Tankard, Census of Inmates in Almshouses and Poorhouses, 1875–1921, record no. 1025, Clinton County Poorhouse; Series A1978, reel 20; New York State Archives, Albany, NY; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed January 2026).

- New York State Department of Health, “William Tankard death entry, 1901,” New York State Death Index, 1880–1956, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed January 2026), citing Certificate Number 16218.

- James Tankard, Census of Inmates in Almshouses and Poorhouses, 1875–1921, record no. 1025, Clinton County Poorhouse; Series A1978, reel 20; New York State Archives, Albany, NY; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed January 2026).

- Ibid.