The grave of Karl Rossi in Schenectady, NY

Source: Find a Grave

Karl Rossi’s granite gravestone lies quietly among those of his family in Vale Cemetery in Schenectady, NY.1 Its inscription lists only his birth and death dates—a modest marker for a life that carried him across an ocean into a land that was often unwelcoming to newcomers. His life captures the story of countless German immigrants who sought belonging in an America that both needed and distrusted them.

Karl’s story begins in Heiligenstadt, Germany when he was born on December 5th, 1877, to parents Georg and Kathrina. Nestled in Thuringia, a region transforming rapidly in the late nineteenth century from a medieval market town to a modern municipality, Heiligenstadt offered opportunity to some but hardship to many. Karl lost his father at nine and his mother twelve years later, leaving him without parental support in a society where wages stagnated and prospects for advancement were narrowing for working-class men amid the disruptions of industrialization.

Seeking stability and opportunity, Karl joined the thousands of Europeans sailing for America. He arrived in New York Harbor aboard the Carpathia on August 27th, 19032—a vessel that, less than a decade later, would become famous for rescuing survivors of the Titanic. Like many Germans, he likely traveled by rail from Thuringia to a North Sea port and then by ferry to Liverpool, the principal hub for transatlantic crossings. His journey placed him among the vast tide of migrants who reshaped American cities in the early twentieth century, leaving behind rural uncertainty for the industrial promise of steady wages and self-made futures.

Three brothers: Henry, Phillip, and Karl Rossi

Source: author’s personal collection

By 1909, Karl had begun to carve out his new beginning, boarding at 609 Cutler Avenue in Schenectady, NY, and working as a toolmaker.3 The city was dominated by General Electric and the American Locomotive Company, both major employers of immigrant labor. Boardinghouses proliferated, offering cheap but crowded accommodations, and German newcomers clustered in certain wards, preserving their language and customs while adapting to American life.4 Karl’s days would have been long and his wages modest, but the hum of German, Italian, and Slavic voices that filled his neighborhood reflected the cosmopolitan rhythm of a city built by migrants.

By 1910, Schenectady’s German community was well established, even as new waves of Italians and Eastern Europeans arrived. Lutheran and Catholic parishes anchored neighborhoods, while Vereine—mutual aid societies—offered fellowship, hosted dances, and provided a safety net for members in need. German-language papers such as Das Deutsche Journal and the Schenectady Herold sustained a shared sense of identity.5 For Karl, these institutions offered comfort and connection, linking the world he had left behind to the one he was building anew.

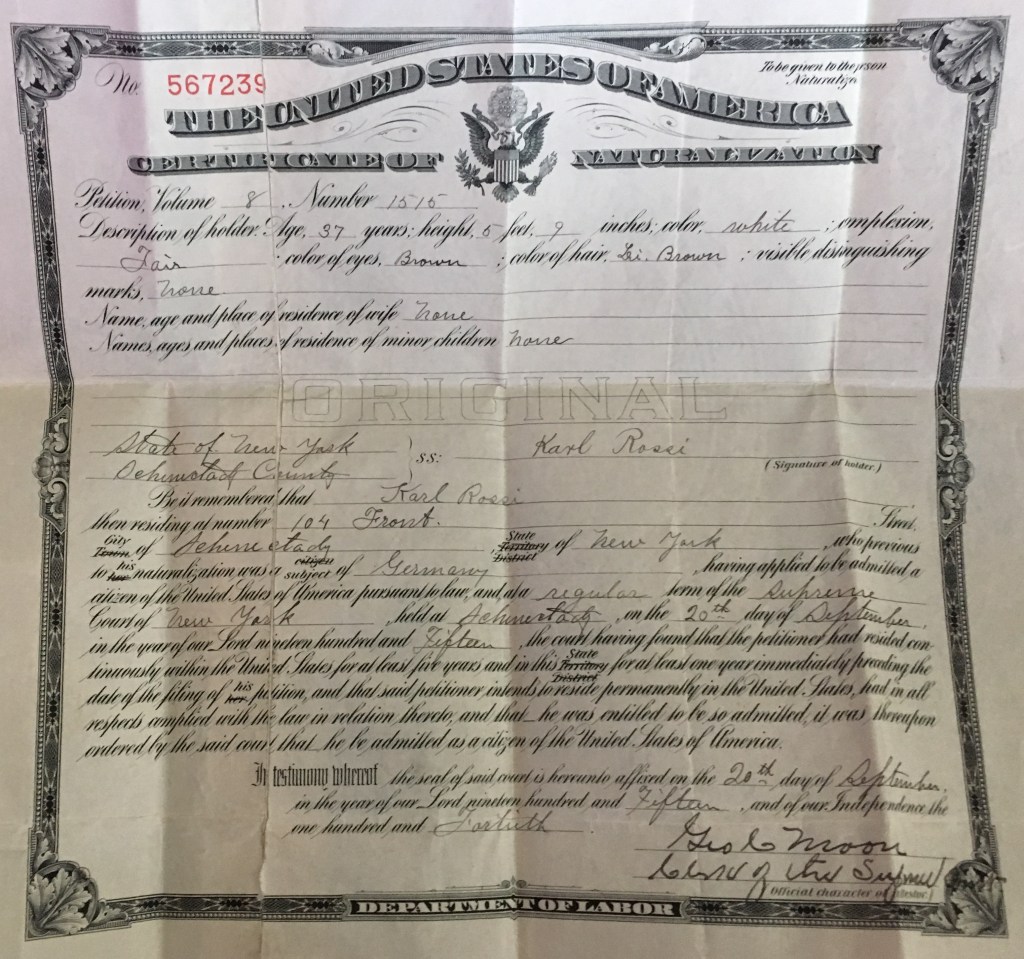

Karl’s 1915 naturalization certificate

Source: author’s personal collection

The shifting nature of life in Schenectady saw Karl living at 1042 Delamont Avenue by 1910. Three years later he was boarding at 821 Hamilton Street. By 1915, he had moved again and was boarding with Margaret Weast and her two daughters at 104 Front Street.6 In the midst of these changes, Karl became secretary and treasurer of S.R. Manufacturing Company, and on September 20th, 1915, took a defining step in his new life when he became a naturalized citizen of the United States.7

Not long after Karl became a citizen, the United States entered The Great War—now fighting against his native Germany. The conflict placed German Americans like Karl in a difficult position. Across the nation, the government’s Committee on Public Information (CPI) fueled anti-German sentiment, casting suspicion on immigrants who were often derided as “Huns” or “spies.” The ensuing campaign for “100 percent Americanism” led to the suppression of German culture: newspapers were closed, schools dropped German from their curricula, and entire communities saw their heritage erased.8 In some towns, German books were burned and street names changed.9 Even prominent figures were not immune—General Electric’s chief consulting engineer, Charles Proteus Steinmetz, himself German-born, was viewed warily for his heritage and political views.10 Such pressures hastened the decline of public German identity, eroding a cultural fabric that had once defined cities like Schenectady. For Karl, still without family or property, the war years must have felt especially precarious.

The S.R. Manufacturing Company offers a glimpse into Karl’s life during Schenectady’s industrial golden age. Operating out of 56 Weaver Street, the firm was a diversified small-scale manufacturer—typical of the city’s entrepreneurial spirit—producing everything from marine engines to everyday goods like clothes-line pulleys. Its flagship product, the “Mohawk” Marine Motor, named for the nearby river, catered to both canal commerce and the region’s growing demand for recreational engines.11 This adaptability enabled S.R. Manufacturing to thrive in the shadow of industrial giants such as GE and ALCO, serving as a modest yet vital part of the city’s manufacturing ecosystem.

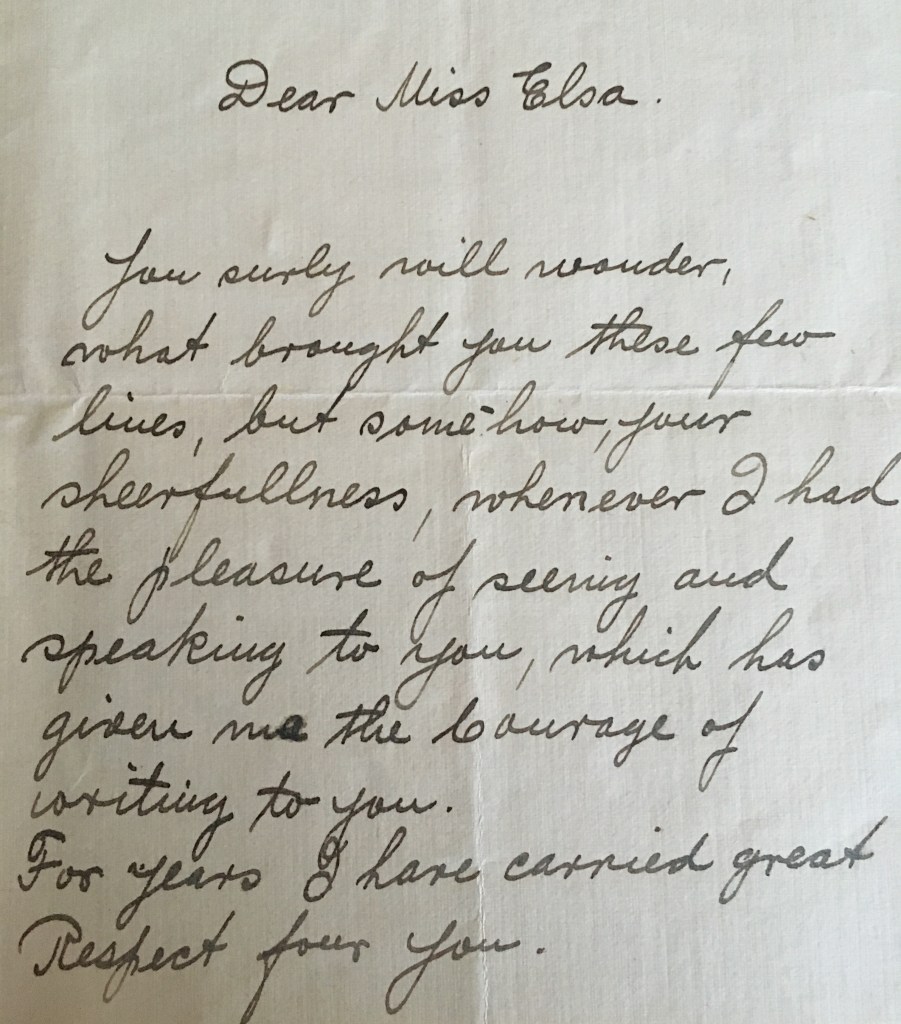

First page of the original letter from Karl to Elsa

Source: author’s personal collection

The 1920 census found forty-one-year-old Karl still living with Margaret Weast and her family while continuing to build the business.12 His purchase of a brick home at 34 North Ferry in Schenectady suggests the business was thriving. While living there, a chance encounter with Elsa Peper, the daughter of a Schenectady family of German descent, would change Karl’s life. The beginning of their courtship survives in a letter he wrote to her:

Dear Miss Elsa,

You surely will wonder, what brought you these few lines, but somehow your sheerfullness [sic], whenever I had the pleasure of seeing and speaking to you, which has given me the courage of writing to you.

For years I have carried great Respect for you.

Next Thursday in the Albany Armory (Albany) Mr. McCormack will give a concert. Would you be so kind of giving me the pleasure of your company.

I am not sure, if you remember my name, but the other day during your Vacation, when you were waiting in Weaver Street for your folks to take home I had a few pleasant words with you so you might know, who is writing these few lines.

A few lines will bring great happiness or should you decide otherwise. Fate must so willed it. Believe me yours sincerely,

Karl Rossi, 34 North Ferry Street13

The letter reflects the conventions of early twentieth-century courtship. At a time when propriety and parental approval carried great weight, written correspondence offered a socially acceptable—and often preferred—means of expressing interest. Historians note that “correspondence courtship” allowed men to express their intentions respectfully while giving women the opportunity to respond privately and with dignity.14 One contemporary guide reminded parents that “Our daughters and our sons are our most precious possessions, are treasures far outweighing gold and gems, and we cannot too closely guard them from mistakes at the outset of their lives.”15 Karl’s tone—measured, cheerful, and deferential—echoed these expectations and conveyed genuine respect. His invitation to a John McCormack concert at the Albany Armory was equally significant: McCormack, the celebrated Irish tenor, drew large immigrant audiences who found in his performances a blend of refinement and sentiment that bridged the distance to the Old World.16

Wedding photo of Karl and Elsa

Source: author’s personal collection

Although little evidence survives of Karl’s courtship with Elsa beyond the initial letter, the relationship clearly flourished: the two were married on June 25, 1924. A wedding announcement in the local paper described the details of their union:

“Elsa S. Peper, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Fred W. Peper of 612 Crane Street, and Karl M. Rossi of 34 North Ferry Street, were married last Wednesday by Rev. Karl Schloede. The bride was attended by Florence Peper and the best man was Alfred Peper. She wore white crepe romaine and shadow lace and carried a shower bouquet of white roses and lilies of the valley. Her attendant wore light blue crepe de chine and carried butterfly roses. Following the ceremony a reception was held at the bride’s home for the immediate members of the family. After a wedding trip south, Mr. and Mrs. Rossi will be at home after July 6.”17

Such announcements were typical of the period. In many immigrant communities, weddings served not only as private milestones but also as public affirmations of heritage and belonging.

Karl and Elsa’s family grew quickly after their marriage. Their first child, Karl Jr., was born in August 1925, followed by daughter Elsa in July 1927 and, later, a son named Alfred in honor of Elsa’s brother. To accommodate their growing household, the Rossis moved to 954 St. David’s Lane in nearby Niskayuna, a home valued at $15,000 by 1930, a sign of their rising prosperity.18

The 1930s brought both hardship and endurance for the Rossi family. In 1930, their son Alfred died, and in 1939 they lost another young child, Philip.19 Although infant and child mortality had declined by this time, it still cast a long shadow over American families. For Karl and Elsa, these losses must have been devastating, yet they also reinforced the centrality of family bonds. Many immigrant families responded to such grief by drawing closer together, finding strength in shared hardship.20 Economic uncertainty compounded their struggles: the 1929 stock market crash ushered in the Great Depression, shuttering factories, slashing shifts, and sending unemployment soaring across Schenectady. Small manufacturers like S.R. Manufacturing suffered as customers delayed purchases or defaulted on credit. Yet not all was sorrow—amid the turmoil, the Rossis welcomed a daughter, Joyce, in 1932.21

Karl’s experience in the 1930s was shaped not only by family but also by the institutions that anchored Schenectady’s immigrant life. German churches offered spiritual solace and reinforced social networks, while mutual aid societies provided health insurance, funeral benefits, and small business loans. Such associations formed vital safety nets during the Depression, embodying the ethic of Familie writ large—community as extended kin. Through participation in these institutions, Karl deepened his ties to both German and American society.

Rossi family circa 1940: Karl Jr and Karl Sr. in the back; Joyce, Elsa, and Elsa in the front

Source: author’s personal collection

By 1940, the Rossi family still lived on St. David’s Lane in Niskayuna. Owning their home suggested that they had weathered the Depression with some stability, yet the census reveals another story: the house’s value had fallen to $5,000, and Karl was working sixty hours a week—among the longest schedules of any neighbor.22 His determination hints at the ongoing effort required to sustain his business through the lingering effects of the Depression.

Even as Karl built a life in America, his ties to Germany endured in the years after World War II. In the immediate postwar period, when food, clothing, and tools were scarce, German Americans often sent care packages—flour, soap, fabric, small tools—to relatives struggling in the ruins of Europe. Historians have shown that this practice was widespread, an expression of enduring family obligation as German Americans wrestled with the belief that Germans, too, had been among Hitler’s victims. Like many immigrants, Karl and Elsa bore both the emotional and financial burden of aiding kin overseas. A letter received from Berlin in March 1949 attests to the impact of their generosity:

Berlin, 20.3.1949

Very honored Mr. Rossi!

I want to hurry and let you know that your food package from 4.12.48 and the clothing package from 17.1.49 arrived here yesterday and today.

I don’t know what words to find in my joy to thank you for your love and attention. The happiness that you once again brought to my home through your gifts is indescribable. All day long there is only one topic and that is: The great admiration for your mercy and the great understanding for our current plight. We are aware that you have an open heart and a strong feeling for your fellow human beings.

The Berlin letter underscores the enduring significance of transatlantic family ties in immigrant life. For German Americans, assisting kin in postwar Germany was both a moral obligation and a reaffirmation of identity and belonging across borders. Karl’s generosity—shaped by his own experiences of hardship and perseverance—reveals how family remained the foundation of his life’s story.

As Karl continued sending aid to family in Germany, he was quietly battling illness. He died at home in Niskayuna on June 3, 1949. Four days later, The New York Times published a brief obituary: “Karl Martin Rossi, partner of the S.R. Manufacturing Company here, died last night at his home after a two-year illness. He had been in the hardware manufacturing business for the last thirty-nine years.”23 By then, Karl had completed the full arc of the immigrant experience—from an orphaned youth in Thuringia to a respected husband, father, and business owner. His journey—marked by perseverance through war, prejudice, and depression—embodies the resilience of countless immigrants who built America’s industrial age not as magnates, but as steadfast craftsmen, neighbors, and parents devoted to family and humanity across borders.

Endnotes

- “Karl Rossi (1879–1949),” Memorial [231441874], Find a Grave, Accessed 10/10/2025, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/231441874/karl_martin-rossi.

- The National Archives in Washington, DC; Washington, DC, USA; Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957; Microfilm Serial or NAID: T715; RG Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004; RG: 85.

- Schenectady City Directory, 1909, Page 311, entry for Karl Rossi; digitized in U.S. City Directories, 1822–1995, database with images, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 10/10/2025).

- Schenectady’s Immigrant Communities in the Late 19th and Early 20th Century, Schenectady County Historical Society Newsletter (Schenectady, NY: Schenectady County Historical Society, 2024), 13.

- Ibid.

- 1910 U.S. Census, Schenectady County, New York, population schedule, Schenectady Ward 7, Enumeration District (ED) 198, sheet 11B/12A, dwelling 272, Dorothy Van Debburg household; digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 10/10/2025); citing National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) microfilm: 1375091. Schenectady City Directory, 1911, Page 488, entry for Karl Rossi; digitized in U.S. City Directories, 1822–1995, database with images, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 10/14/2025). Schenectady City Directory, 1915, Page 451, entry for Karl Rossi; digitized in U.S. City Directories, 1822–1995, database with images, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 10/14/2025).

- Certificate of Naturalization of Karl Rossi, Petition Volume 9, No. 1515, issued by the Supreme Court of New York, September 20, 1915, copy in the possession of the author.

- Mary J. Manning, “Being German, Being American: In World War I, They Faced Suspicion, Discrimination Here at Home,” Prologue 46, no. 2 (Summer 2014): 10. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2014/summer/being-german-being-american

- Library of Congress, “Shadows of War: German Americans during World War I,” accessed September 20, 2025, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/german/shadows-of-war/.

- George Wise, “Proteus and the Great War,” Schenectady County Historical Society Newsletter 61, nos. 4-6 (April-June 2017): 6.

- Schenectady City Directory, 1919, Page 796, advertisement for “The S-R Manufacturing Company); digitized in U.S. City Directories, 1822–1995, database with images, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 10/14/2025). Schenectady City Directory, 1927, Page 761, advertisement for “The S.R. Manufacturing Co); digitized in U.S. City Directories, 1822–1995, database with images, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 10/14/2025).

- 1920 U.S. Census, Schenectady County, New York, population schedule, Schenectady Ward 1, Enumeration District (ED) 127, sheet 3A, dwelling 23, family 23, Margaret Weast household; digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 10/11/2025); citing National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) microfilm publication T625, roll 1262.

- Karl Rossi to Elsa Peper, circa 1922, copy in the possession of the author.

- Karen Lystra, Searching the Heart: Women, Men, and Romantic Love in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 158–62.

- Margaret Elizabeth Munson Sangster, Good manners for all occasions, including etiquette of cards, wedding announcements and invitations (New York: Cupples & Leon company, 1919), 78, https://archive.org/details/cu31924014059103.

- Scott Spencer, “Wheels of the World: How Recordings of Irish Traditional Music Bridged the Gap between Homeland and Diaspora,” Journal of the Society for American Music 4, no. 4 (November 2010): 437–449.

- Newspaper wedding announcement clipping for Elsa S. Peper and Karl M. Rossi, June 1924, copy in the possession of the author.

- 1930 U.S. Census, Schenectady County, New York, population schedule, Niskayuna Township, Enumeration District (ED) 47-9, sheet 38A, dwelling 993, family 1030, Karl Rossi household; digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 10/14/2025); citing National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) microfilm publication, roll 2341378.

- “Alfred Rossi (?–1930),” Find a Grave Memorial ID 167504772, accessed 10/15/2025, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/167504772/alfred-rossi. “Phillip Rossi (?–1939),” Find a Grave Memorial ID 167504771, accessed 10/15/2025, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/167504771/philip-rossi.

- Kathleen Neils Conzen, “Ethnicity as Festive Culture: Nineteenth-Century German America on Parade,” in The Invention of Ethnicity, ed. Werner Sollors (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 47–76.

- 1940 US census, Schenectady County, New York, population schedule, Niskayuna Township, page 11B, family 38, Karl Rossi household; digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing Roll: m-t0627-02774.

- Ibid.

- Maximilian Klose, “Molding Heritage Through Humanitarian Aid: German-Americans, Nazism, and Debates on Postwar German Suffering and Guilt,” Journal of Contemporary History 59, no. 3 (2024).

- Letter to Karl Rossi, March 20, 1949, copy in the possession of the author.

- “Karl M. Rossi,” New York Times, June 7, 1949, sec. Archives, https://www.nytimes.com/1949/06/07/archives/karl-m-rossi.html.

How / when did you encounter the Karl Rossi story, Darren? I’m assuming you’ve visited Vale Cemetery–did that happen during one of your rides?

LikeLike

Karl’s story is one tied to our family. The youngest Rossi daughter, Joyce, married James Maryea in the early 1960s. James was the adopted son of Genevieve and Arthur Maryea. Their only biological child was our maternal grandmother.

LikeLike