Frederick Fitch’s grave in Maple Hill Cemetery, Champlain, NY

Source: author’s personal collection

Frederick Fitch’s grave lies tucked away in Maple Hill Cemetery on a small rise bordered by the steady hum of traffic along a state highway in Champlain, New York. There he rests beside his wife, their unadorned markers recording only their names and years, the brief inscriptions fading beneath lichen and age. Nothing in those simple inscriptions suggests the long journey that brought them to Champlain from New England or the changing rural world through which they passed. Yet Frederick’s life traces the broader story of many men born in the closing years of the eighteenth century—men who cleared new farms, raised families on uncertain land, and labored through the slow transformation of nineteenth-century America.

Frederick Fitch was born when the young American republic was still defining its ideals. He came into the world in Coventry, Connecticut, on February 27, 1785, the son of John and Anna Fitch—four years before the adoption of the Constitution by the United States. His father, a veteran of the Revolutionary War, was the youngest son in a world where younger sons faced challenges. Primogeniture, though legally weakened after the Revolution, remained powerful in custom, still steering land toward eldest sons and forcing younger ones to find their own path. Historian Paul E. Johnson has described the moral and social pressure this created among New England farmers: “New England men…grew up confronting two uncomfortable facts. The first was the immense value their culture placed on land ownership… the second was that in the late eighteenth century increasing numbers of men owned no land.”1 As Johnson’s observation suggests, opportunity was scarce in older towns. In Coventry’s population of 2,130 in 1790, younger men like John Fitch had little chance of securing a homestead. By 1800, he had moved his family, including 15-year-old Frederick, to Chittenden County, Vermont, where he was documented as farming his own land by 1820.2 John also served as a constable and justice of the peace—a man who had fought for the nation’s creation and then returned home to uphold its laws.3 For men like John Fitch, landownership was both the reward and the proof of independence. In the agrarian imagination of early America, land was not merely property; it was the moral foundation of citizenship.

By the time Frederick reached adulthood, he faced the same challenge his father had known: farmland in Vermont was dwindling, and his older brother, John, would eventually inherit the family farm. In the early nineteenth century, the quest for land drew New England’s sons westward and northward in search of independence and opportunity. The frontier, once bounded by the Hudson River, had shifted into the Adirondack borderlands and the northern reaches of New York, Vermont, and Maine—regions whose forests and meadows offered the independence that New England’s settled towns could no longer provide.4

Frederick’s own journey followed that course. On February 10, 1813, at age twenty-seven, he married Nancy Bunker in Huntington, Vermont, one of the mountain towns that had flourished during the state’s post-Revolutionary settlement boom.5 Their early years were likely marked by hardship and hope in equal measure. By the time their first children—Adaline, Theodore, and Henry—were born before 1816, the couple was looking toward the Champlain Valley. By 1820, Frederick and Nancy followed his older brother Solomon across the lake to settle in Champlain, a swiftly expanding agricultural settlement at Clinton County’s northern extremity on the Canadian border.6

Champlain was a frontier town in transition when Frederick arrived. Between 1810 and 1820, its population exploded from 1,210 residents to 1,618—a 34% increase in a single decade.7 Roads were poor, and winters severe, but the land was cheap and fertile, and for men like Frederick, that was enough. In the 1820 census, he appears as a farmer, head of a household of five, with two members “engaged in agriculture.”8 It was the modest beginning of a dream that had defined generations: the transformation of wilderness into home.

To the modern reader, the phrase “independent farmer” may evoke pastoral simplicity, but in the 1820s it carried a dense web of moral, religious, and political meaning as well. The value of a freehold farm extended well beyond its acres; it sustained a moral order that defined a man’s autonomy, his role within the family, and his place in the republican nation. For men like Frederick, these ideals were not abstractions but the framework of daily life. Independence meant steady labor. His children grew alongside the farm, contributing their hands to the cycles of planting and harvest. By 1830, nine people lived in the household—parents, sons, and daughters—forming the core of the agricultural workforce centered in the household. By 1840, that number had grown to eleven. Their daily lives would have followed the rhythm of the northern seasons: clearing fields in spring, haying and harvesting through summer and fall, and enduring long winters of mending tools, carding wool, and cutting firewood.9

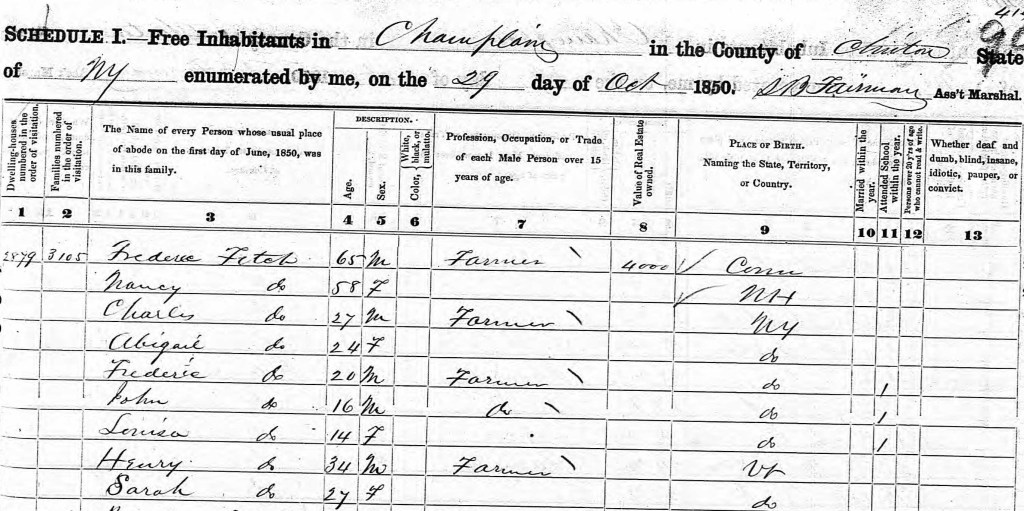

The Fitch household in 1850 that included Frederick, Nancy, and their children and daughter-in-law Sarah

Source: 1850 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township.

By the 1850s, the family’s long years of labor had matured into a measure of stability—even as the rural world around them was beginning to shift.10 The 1850 federal census records a nine-person household ranging in age from 14 to 65: Frederick (65) and his wife Nancy (58); their son Henry (34) and his wife Sarah (27); sons Charles (27), Frederick Jr. (20), and John (16); and daughters Abigail (24) and Louisa (14). Four men in the household—Frederick, Henry, Charles, and Frederick Jr.—were listed as farmers, a concentration of adult male labor that helps explain the family’s relative prosperity. The farm itself was valued at $4,000, a substantial figure for Clinton County and one notably above the Champlain township average of $2,763.11

The 1850 agricultural census reveals a farm organized with care and conscious balance. Fitch’s one hundred acre operation—eighty acres improved and twenty in woodlot or pasture—placed him in roughly the upper 40% of Champlain farms by size. His ratio of improved to unimproved land was notably more intensive than the township average (seventy-five improved to fifty-six unimproved), indicating a farm more fully cleared and actively cultivated than most of his neighbors’. This level of improvement likely reflects the presence of four adult men in the household, whose labor made such sustained clearing and cultivation possible. Fitch’s livestock holdings further point to a diversified and comparatively prosperous enterprise. With three horses, seven milk cows, seven other cattle, and thirty sheep, the Fitch herd exceeded local averages in every category except horses, marking the family as part of the township’s substantial middle tier of agricultural producers.12

The presence of sheep offers another window into the household economy of the Fitch farm. Of the 220 farmers in Champlain in 1850, 166 (roughly 75%) kept sheep. Frederick’s flock of thirty placed his household in the top 15% of owners with wool production even higher. Maintaining such a sizable flock was a deliberate choice enabled by the household economy fueled by the women who traditionally bore responsibility for wool processing and textile preparation. Wool production would have provided the Fitch family with yet another commodity for exchange, one that could be bartered for skilled services such as blacksmithing or coopering. In this way, the flock reflects not only household capability but also the family’s strategic engagement with the local economy.13

The farm’s cropping pattern likewise reflects a household transitioning from self-sufficient yeomanry to active participants in a changing market economy. Of the 220 farms in Champlain, all but sixteen harvested wheat in 1850; even in this near-universal crop, the Fitch family’s yield of 170 bushels placed them within the top 15% of local producers. Their 250 bushels of oats similarly exceeded the town average, ranking them in roughly the top 20%. In butter and cheese production, however, the Fitch household reached its highest standing: their butter output placed them among the top 10% of producers in Champlain, while their cheese production ranked in the top 16%—almost certainly the result once more of a household economy driven by the Fitch women.14 In practical terms, the family not only sustained itself comfortably but also produced surpluses for sale, revealing their growing engagement with the market economy.

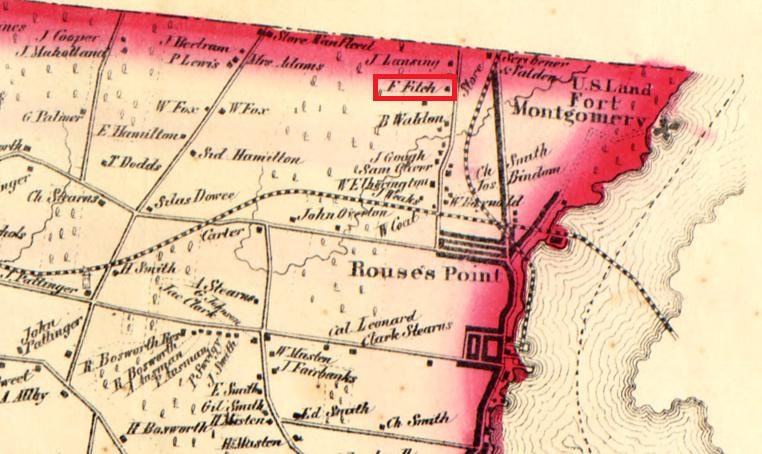

1856 map of Champlain showing the location of the Fitch farm nearby to the railroad and Canadian border

Source: Ligowsky, A. Map of Clinton Co., New York. Philadelphia: O.J. Lamb, 1856. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2009583837/.

As Frederick achieved independence, the world around him was changing. By the 1850s, upstate New York was no longer the frontier. The Ogdensburg and Lake Champlain Railroad, with its eastern terminus ending in Champlain within sight of the Fitch farm, connected the farmlands of northern New York to rapidly growing cities in the northeast and southern Canada.15 Market integration was transforming the region, binding farmers to distant prices and urban demand. The ideal of the self-sufficient yeoman was giving way to the reality of a competitive market economy as the expanding Midwest and improved rail transport flooded eastern markets with cheaper grain, forcing smallholders to specialize or scale back.16

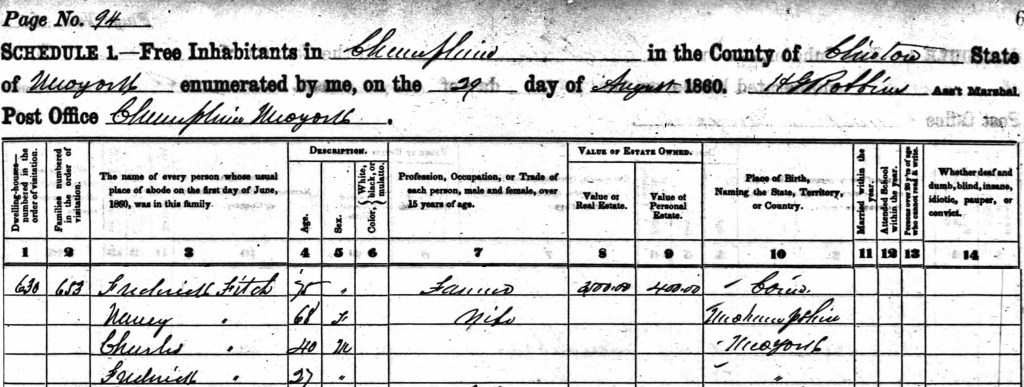

The broader regional trends became more visible in the 1860 census, where the value of Fitch’s farm had declined modestly to $3,500 from $4,000 a decade earlier. More significant than the decrease in land value, however, was the contraction of the household itself. By 1860, only four people remained at home: Frederick and Nancy, along with two of their sons, Charles and Frederick Jr. As sons and daughters married or moved away to establish their own households, the loss of labor—particularly the women who had supported dairying and textile production—caused the farm’s outputs to align more closely with township averages in both livestock and crop yields. The number of horses fell from three to two, and milk cows from seven to four. The sheep flock, which had numbered thirty in 1850, had fallen to five, a clear sign that the labor-intensive wool work could no longer be sustained.17 This change also reflected broader economic shifts: as textile production became increasingly industrialized in New England, the Fitch family would no longer rely on household wool as a viable commodity for trade.

In nearly every respect, Fitch’s production now fell slightly below Champlain’s township averages. His crop yields tell the same story: thirty-six bushels of wheat (compared to a town average of forty-six), forty of corn (below the average of sixty-nine), and 500 of oats (somewhat above the typical 436). The continued emphasis on oats may indicate a pragmatic shift toward fodder crops to support a reduced herd rather than a focus on commercial grain sales. His potato harvest (100 bushels, against a local mean of 182) and his butter production (400 pounds, compared to a township average of 380)—further reflect a scaled-back operation aimed at subsistence with limited surplus. Together, these figures depict a farm adjusting to diminishing household labor and the aging of its patriarch, rather than one actively expanding or seeking profit in an increasingly competitive agricultural economy.18

Such contraction was not unusual. Across the North, aging farmers often found themselves unable to keep pace with the accelerating modernization of agriculture. Mechanization, improved plows, reapers, and threshers, and new market-oriented breeds favored younger men with capital and ambition. The decline in Fitch’s equipment value (from $100 in 1850 to $75 in 1860) illustrates this generational divide.19 Frederick was nearing the end of his working life, still maintaining the land that had sustained his family for more than four decades, but now doing so on a reduced scale. His two sons almost certainly managed the physically demanding work their father could no longer perform.20

Seen through the 1860 census, the Fitch farm captures a pivotal moment in the transformation of northern agriculture: a household that had begun in the spirit of yeoman self-sufficiency now operated within an increasingly integrated market economy. No longer was the household economy a primary driver in decision making. The adjustments visible in Frederick’s final decade—the contraction of livestock, shifts in cropping patterns, a move toward selective specialization, and a smaller household—suggest not simple decline but a farmer responding pragmatically to changing prices, labor shortages, and regional competition while his family aged and began to seek out their own opportunities. Even late in life, Frederick was not merely enduring agricultural change but negotiating it, adapting his practices to the new economic currents reshaping rural New York.

The 1860 census showed Frederick’s household shortly before he passed away in July 1860

Source: 1860 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township.

By the time Frederick died in Champlain on July 27, 1860, at the age of 75, the society he had helped build was giving way to a new one. The Civil War loomed, ushering in an age of industrialization, urban growth, and restless movement that favored younger men better positioned to adopt the increasingly capital-intensive practices reshaping American agriculture. Some pressed farther west, pursuing the same agrarian dream that had once brought Frederick to the Champlain frontier—a chance to own land, raise a family, and live by their labor. Viewed through census data and agricultural returns, Fitch’s life may appear ordinary, yet within those numbers lies the story of a man whose choices reflected the broader economic transformation of the American countryside. To read Frederick’s story is to glimpse a central thread in the American experience: the enduring search for rootedness in a world of movement. That legacy endures in Champlain today, where the Fitch farm remains in the hands of his descendants—a rare continuity in a region where most family farms have long since vanished.

Endnotes

- Paul E. Johnson, “The Modernization of Mayo Greenleaf Patch: Land, Family, and Marginality in New England, 1766–1818,” The New England Quarterly 55, no. 4 (December 1982): 489–490.

- 1800 US census, Chittenden County, Vermont, population schedule, Huntington Township, page 1, John Fitch household, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M32, Roll 51. 1820 US census, Chittenden County, Vermont, population schedule, Huntington Township, page 1, John Fitch household, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M33, Roll 127.

- “Chittenden County,” The Vergennes Gazette and Vermont and New-York Advertiser (Vergennes, Vermont, USA), November 1, 1798, 3, https://www.newspapers.com/.

- See Alan Taylor, Liberty Men and Great Proprietors: The Revolutionary Settlement on the Maine Frontier, 1760–1820 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990) for an overview of frontier settlement in the early republic. Taylor focuses on Maine but highlights the moral as well as economic motives for migration.

- “Nancy Bunker,” entry in “Geneanet Community Trees Index” 2022, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025), record 7821956846.

- 1820 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Frederick Fitch household, page 3, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M33, Roll 66.

- Clinton County NYGenWeb, “The 1810 Census for Clinton County, New York,” accessed November 16, 2025, https://clinton.nygenweb.net/1810.htm. U.S. Census Office, Census for 1820 (Washington, DC: U.S. Census Office, 1821), 22, table of aggregates for New York State, Town of Champlain; https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1821/dec/1820a.html.

- 1820 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Frederick Fitch household, page 3, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M33, Roll 66.

- 1830 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Frederick Fitch household, page 5, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M19, Roll 85. 1840 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Frederick Fitch household, page 15, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication Roll 276.

- See Christopher Clark, The Roots of Rural Capitalism: Western Massachusetts, 1780–1860 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1990) for an overview of the broader social, economical, and ideological changes seen in a rural community from 1790-1860.

- 1850 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Frederick Fitch household, dwelling 2879 family 3105, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll 490, Page: 454a.

- 1850 U.S. Census, Agricultural Schedule, Town of Champlain, Clinton County, New York, Frederick Fitch farm, page 2, line 35, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Doherty, Lawrence. “General History of the O. & L. C. Railroad.” The Railway and Locomotive Historical Society Bulletin, no. 58A (1942): 91–98. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43504337.

- For more information on how Midwestern grain and the introduction of railroads forced changes to eastern agriculture, see William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1991).

- 1860 U.S. Census, Agricultural Schedule, Town of Champlain, Clinton County, New York, Frederick Fitch farm, page 6, line 2, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- 1860 US census, Clinton County, New York, population schedule, Champlain Township, Frederick Fitch household, dwelling 630 family 653, digital image, Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 2025); citing National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll 653_736, Page: 657.